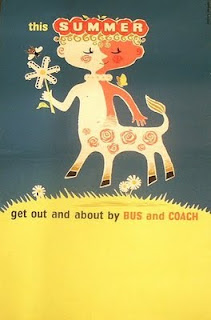

The Bundesrat (Germany’s upper house of the legislature) has voted to remove long-standing protections on the national railway network, the Deutsche Bahn, to allow competition for commuter and holiday travel from long-distance, inter-city bus and coach companies. After much debate and research, parliament, risking the displeasure of this established institution, determined that the virtual monopoly should be allowed to lapse, since private enterprise could offer travelers alternatives adhering to environmental standards, at a discount and with greater flexibility.

Saturday 3 November 2012

timetable or free-on-board

catagories: 🇩🇪, 🚋, environment, transportation, travel

four-square and eight-bit

Considering the estimable impact and pioneering influence the surprisingly simple and intuitive yet habit-forming diversion Tetris had on the video game landscape, it seems ironic that the concept and programming, built in turn off of earlier mathematical models and gaming traditions that go back to antiquity, Connect-Four or Penta (that glass bead game with the scroll for the playing area that they sold at Pier One), emerged not from the US or Japan but rather the Moscow Academy of Computer Sciences in 1984, spreading to Western markets prior to glasnost and faster than conventional diplomacy in just a matter of months. Did you know that tetrominoes fall in accordance with the laws of gravity, accelerating in proportion to the height of the stacks below?

Friday 2 November 2012

simulacra, simulcast or a night at the opera

Although this installation is not part of the historic opera house in Munich but the State Opera of Saxony in Dresden, I thought it was a comical touch to put one of the world’s first “digital” clocks (with Roman numerals that scrolled by the minutes and hours) above the stage—I suppose so patrons could be discrete about wondering when the show would end, without having to dig out their pocket-watches. I do think it’s important that it be live, however, and an occasion for dressing-up—even if one is only going as far as the living-room. Opera was never meant to be elitist and inaccessible and was traditionally quite the opposite, but I think now people shy away from the commitment of time and would rather call it so. What do you think? Is this offering expanding the audience, like a pay-per-view match or post-game camaraderie, or is it like putting church on television and only mildly engaging?