Mental Floss disabuses us of some of our favourite misattributed or completely made up great quotations with a studied collection of sayings that go rather deeply into the origins of those things we wish our heroes had said. One of the best stories is about how Abraham Lincoln supposedly proclaimed that “When you look for the bad in mankind expecting to find it, you surely will.”

This wise if not somewhat Pollyanna-ish line comes to us not from the great statesman but rather via the marketing geniuses at Disney studios, producing a film version of the book Pollyanna, whence at the treacly and campy conclusion, the little heroine opens the locket of her dead father to discover this inscription. The Disney Brothers love it and had hundreds of souvenir lockets commissioned and sold at gift shops. When the writer-director who’d made up the quotation discovered this misattribution spread, to his great dismay, the studio had the unsold trinkets recalled. Also Freud never said “sometimes a cigar is just a cigar” and was doctrinairely against the idea of suggesting otherwise. What are your favourite supposed pithy quotes that turned out to be fictions?

This wise if not somewhat Pollyanna-ish line comes to us not from the great statesman but rather via the marketing geniuses at Disney studios, producing a film version of the book Pollyanna, whence at the treacly and campy conclusion, the little heroine opens the locket of her dead father to discover this inscription. The Disney Brothers love it and had hundreds of souvenir lockets commissioned and sold at gift shops. When the writer-director who’d made up the quotation discovered this misattribution spread, to his great dismay, the studio had the unsold trinkets recalled. Also Freud never said “sometimes a cigar is just a cigar” and was doctrinairely against the idea of suggesting otherwise. What are your favourite supposed pithy quotes that turned out to be fictions?

Friday 16 January 2015

churchillian drift

Thursday 15 January 2015

jail-break or walled-garden

Though today’s conversation has adopted such colourfully metaphoric language, the same problems of communication dominated by a few industry giants, privacy and consumer-protection have a history, lively and just as shameful and grasping, that goes back at least to the advent of telephony and probably reaches much further back with the implements, tried and true, of blacklisting, censorship and charters. Before the United States recognised and rejected the monopoly that Bell conglomerate had on the public’s telephone lines, people and businesses did not purchase their telephones but rather rented units from Bell with a monthly subscription—pretty much the same situation we have today, being untethered physically but still locked into contracts that are bundled with gadgets and accessories tied to the service.

catagories: 🇺🇸, 🥸, antiques, networking and blogging, technology and innovation

epimetheus/prometheus

Happy Mutant and accomplished author in his own right Cory Doctorow extolls the latest fantasy novel from Jo Walton. Not only does this plot in which a time-traveling Athena, goddess of Wisdom, assembles all the faithful from all ages who yearned to live in the Utopia of Philosopher Kings sound really intriguing, her other works, which include award-winning alternate histories, expositions on ancient lore and future-oriented works of science fiction, are appealing to my curiosity already.

I think I’ll have to check these out. In the Platonic dialogue Protagoras—between Socrates and the famous eponymous sophist, who’s profession is to make the weaker argument the stronger, we are told that the second-generation twin titans were charged with endowing all of creation with their individual excellences, like slyness for the fox, courage for the lion, wisdom for the owl and so on. Thoughtful and generous but of course lacking foresight, however, when Epimetheus (whose name means backward-looking or hindsight) came to endow man with positive attribute, he realised that his bag of gifts was empty. This oversight was what prompted his brother, Prometheus, to steal fire and the civilising arts from the Olympian gods in order to give mankind some redeeming qualities and a skill-set for survival.

I think I’ll have to check these out. In the Platonic dialogue Protagoras—between Socrates and the famous eponymous sophist, who’s profession is to make the weaker argument the stronger, we are told that the second-generation twin titans were charged with endowing all of creation with their individual excellences, like slyness for the fox, courage for the lion, wisdom for the owl and so on. Thoughtful and generous but of course lacking foresight, however, when Epimetheus (whose name means backward-looking or hindsight) came to endow man with positive attribute, he realised that his bag of gifts was empty. This oversight was what prompted his brother, Prometheus, to steal fire and the civilising arts from the Olympian gods in order to give mankind some redeeming qualities and a skill-set for survival.

catagories: 📚, myth and monsters, networking and blogging, philosophy

Wednesday 14 January 2015

ch-ch-ch-ch-changes

vertreibung oder flüchtlingsthematik

A small village near Weimar, the city that hosted Goethe and Schiller, Bauhaus and the Weimar Republic, is facing some sharp criticism over its suggestion to house refugees in the officers' barracks of the Buchenwald Concentration Camp. There unspeakable horrors associated with the memories of this place, and ironically it seems that our memory has become quite a feeble and atrophied thing. The immigration question is a complex one, but so is Germany’s relation to its past—much more so. Do Germans yet have guilt to discharge from the first half of the twentieth century? Surely, as do many of us—but does this make them to feel grudgingly obligated to accept more and more evacuees? That’s harder to answer—as with the Wirtschaftswunder that characterized Germany’s rebuilding and recovery after the wars ended was made possible to a very large extent through its guest worker programme, many also argue that Germany needs an infusion of a young population to sustain its present and retiring work-force and that Germany on balance benefits from immigration.

I also feel that we are prone to lose our perspective as well: we’re welcoming in these people who’ve mostly been on the run from poverty and violence.

Mostly—and I think we choose to focus on those exceptions and malingerers. We also forget that while the sites of former concentration camps are sacred places, they were not recognized and consecrated as such right away and were regarded very differently depending on whether one found himself in East or West. Buchenwald was used by the Soviets initially as an internment camp for Nazi prisoners-of-war—although political-dissidents were also held there; Dachau and other locations in West Germany was first used to contain Germany’s own refugee crisis. Some fourteen million ethnic Germans were forcibly expelled from territories either ill-gotten and taken back (like Hungary, Czechoslovakia, Romania and Yugoslavia), lands that had been historically German, like much of Prussia that went to Poland and the Soviet Union, for centuries and other European cities where they were no longer welcome, like Amsterdam, were resettled in a Germany in ruins. Not only did the expelled Germany have to leave everything behind, they also faced the prospect of starting all over in a homeland that maybe was not at all familiar to them—their families perhaps living abroad for generations, spoke differently, had strange mannerisms, didn’t eat proper German food and were failing to integrate—and try to live among a population that if not outright hostile to the refugees were themselves struggling and barely had enough to provide for themselves, to say nothing for these newcomers. In the 1950s, once these crises had somewhat subsided, the regimes of the two Germanys took different positions on how the past was to be remembered. East Germany was quicker to turn Buchenwald and other sites into memorials and strongly encouraged people to visit, especially school-children, to face the incomprehensible and dread past. Whereas, in the West, the subject remained uncomfortable and while not going ignored or unexplored, talk was taboo for a long time and it really was not until Reunification that the public became more willing to confront their autobiographies. Perhaps empathy is yet harder to face.

Mostly—and I think we choose to focus on those exceptions and malingerers. We also forget that while the sites of former concentration camps are sacred places, they were not recognized and consecrated as such right away and were regarded very differently depending on whether one found himself in East or West. Buchenwald was used by the Soviets initially as an internment camp for Nazi prisoners-of-war—although political-dissidents were also held there; Dachau and other locations in West Germany was first used to contain Germany’s own refugee crisis. Some fourteen million ethnic Germans were forcibly expelled from territories either ill-gotten and taken back (like Hungary, Czechoslovakia, Romania and Yugoslavia), lands that had been historically German, like much of Prussia that went to Poland and the Soviet Union, for centuries and other European cities where they were no longer welcome, like Amsterdam, were resettled in a Germany in ruins. Not only did the expelled Germany have to leave everything behind, they also faced the prospect of starting all over in a homeland that maybe was not at all familiar to them—their families perhaps living abroad for generations, spoke differently, had strange mannerisms, didn’t eat proper German food and were failing to integrate—and try to live among a population that if not outright hostile to the refugees were themselves struggling and barely had enough to provide for themselves, to say nothing for these newcomers. In the 1950s, once these crises had somewhat subsided, the regimes of the two Germanys took different positions on how the past was to be remembered. East Germany was quicker to turn Buchenwald and other sites into memorials and strongly encouraged people to visit, especially school-children, to face the incomprehensible and dread past. Whereas, in the West, the subject remained uncomfortable and while not going ignored or unexplored, talk was taboo for a long time and it really was not until Reunification that the public became more willing to confront their autobiographies. Perhaps empathy is yet harder to face.

Tuesday 13 January 2015

pastebin or le grand-large

Though I think, especially in the aftermath of America’s latest film critic and the associated retribution even though responsibility was not clear, that it always wise to assume that the world’s security agencies are always ready to pull a wise one on their citizens and propagandise and exploit any crisis or tragedy towards those ends, it is a stance just as specious as having total communication and movement surveillance and stripping naked all vestments of privacy would result in absolute safety and harmony as America and its accomplices wanting to own the all the wires.

vis viva or élan vital

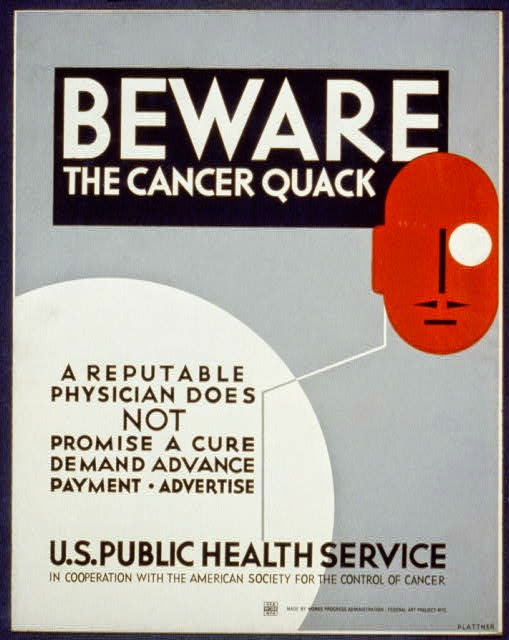

The director of Sigmund Freud’s out-patient clinic in Vienna, influential and controversial to contemporaries, was called Wilhelm Reich and due to later public shaming by an agency of the US government is nearly unknown except for a few of his kookier traces. Reich authored many respected works on mass-hysteria, including exploring why people were enervated by fascists and suddenly found it acceptable to participate in mob activities like biblioclasm (book-burning) and worse, linked poverty to mental health, hypnosis, developed what became the concepts of bio-feedback, body-language and Gestalt therapy (personal accountability), massage therapy and spoke very frankly about sexuality and inhibitions.

After the violent coup that elevated Hitler to power, Reich and many other Germans fled to Norway—including future Chancellor Willy Brandt—and Reich, continuing his research, solicited volunteers, Brandt among them, to make love whilst attached to an oscilloscope and study what sorts of voltage was measured. As the war engulfed Europe, Reich immigrated to the United States, sponsored by the psychiatry school of Columbia University—which did not turn out like Operation Paperclip. It was in New York that Reich first described his Orgone theory—which was basically the same notion as æther or the all-pervading Force or Chi, and imbalances in orgone (named after the orgasm, and not unlike Freud’s libido ideas) radiation led to all human ailments, disease and mental disorders. Reich met with compatriot Albert Einstein and tried to convince him of the efficacy and truth behind his conclusions—possibly under the pretext that the Allies such harness the power of this mysterious metaphysical element before the Nazis discovered it. Orgones could also be used to control the weather. Though Einstein heard him out and even tried to recreate his unscientific experiments, ultimately debunking them because of sloppy control-conditions, Einstein probably thought Reich was a touch looney and this encounter may have begun the unhinging of his professional reputation. Undeterred, Reich continued his experiments, which seemingly innocently enough, consisted of placing volunteers (although sometimes seriously ill people too that fell for quackery) in what was essentially a Faraday cage, a metal shield from outside interference that kept internal energies inside, called Orgone Accumulators for long periods, naked, to restore their natural equilibrium. Failing to get back into academia, Reich decided to purchase a farm in the state of Maine, naming it Orgonon, which included laboratories, treatment areas, a conference centre and an observatory for UFO sightings.

After the violent coup that elevated Hitler to power, Reich and many other Germans fled to Norway—including future Chancellor Willy Brandt—and Reich, continuing his research, solicited volunteers, Brandt among them, to make love whilst attached to an oscilloscope and study what sorts of voltage was measured. As the war engulfed Europe, Reich immigrated to the United States, sponsored by the psychiatry school of Columbia University—which did not turn out like Operation Paperclip. It was in New York that Reich first described his Orgone theory—which was basically the same notion as æther or the all-pervading Force or Chi, and imbalances in orgone (named after the orgasm, and not unlike Freud’s libido ideas) radiation led to all human ailments, disease and mental disorders. Reich met with compatriot Albert Einstein and tried to convince him of the efficacy and truth behind his conclusions—possibly under the pretext that the Allies such harness the power of this mysterious metaphysical element before the Nazis discovered it. Orgones could also be used to control the weather. Though Einstein heard him out and even tried to recreate his unscientific experiments, ultimately debunking them because of sloppy control-conditions, Einstein probably thought Reich was a touch looney and this encounter may have begun the unhinging of his professional reputation. Undeterred, Reich continued his experiments, which seemingly innocently enough, consisted of placing volunteers (although sometimes seriously ill people too that fell for quackery) in what was essentially a Faraday cage, a metal shield from outside interference that kept internal energies inside, called Orgone Accumulators for long periods, naked, to restore their natural equilibrium. Failing to get back into academia, Reich decided to purchase a farm in the state of Maine, naming it Orgonon, which included laboratories, treatment areas, a conference centre and an observatory for UFO sightings.

For all his eccentricities, Reich received little bad press while on the ranch and those in the psychosomatic medical community still though highly of his earlier writings. One magazine interview propelled his theories to national attention, after the war had ended, and Reich became a target of the US Federal Trade CommisSion (FTC) and the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for medical fraud and possible sex-trafficking. Interstate sales of orgone accumulators and printed materials that espoused Reich’s teachings were banned. A federal officer, posing as a client, asked Reich to ship him an accumulator, thus framing him. One of Reich’s final feats was saving the local blueberry harvest by creating a cloud-bursting device that beamed positive orgone radiation into the sky and ended the drought. Farmers were pleased with the results. The sentence handed down was harsh and provided for prison time and the destruction of Reich’s research facility, all orgone accumulators and his publications. FDA agents were present at Orgonon to supervise the destruction carried out by Reich’s friends and associates with axes and a bonfire, with Reich made to watch. After this unrepentant beastliness, accused of being delusional and paranoid and worse, Reich died while in jail, a cell being no proper accumulator. There was a resurgence in interest in Wilhelm Reich in 2008, fifty years after his death, a vault was opened at a medical library of the campus of Harvard University that held an archive of his unpublished papers.

For all his eccentricities, Reich received little bad press while on the ranch and those in the psychosomatic medical community still though highly of his earlier writings. One magazine interview propelled his theories to national attention, after the war had ended, and Reich became a target of the US Federal Trade CommisSion (FTC) and the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for medical fraud and possible sex-trafficking. Interstate sales of orgone accumulators and printed materials that espoused Reich’s teachings were banned. A federal officer, posing as a client, asked Reich to ship him an accumulator, thus framing him. One of Reich’s final feats was saving the local blueberry harvest by creating a cloud-bursting device that beamed positive orgone radiation into the sky and ended the drought. Farmers were pleased with the results. The sentence handed down was harsh and provided for prison time and the destruction of Reich’s research facility, all orgone accumulators and his publications. FDA agents were present at Orgonon to supervise the destruction carried out by Reich’s friends and associates with axes and a bonfire, with Reich made to watch. After this unrepentant beastliness, accused of being delusional and paranoid and worse, Reich died while in jail, a cell being no proper accumulator. There was a resurgence in interest in Wilhelm Reich in 2008, fifty years after his death, a vault was opened at a medical library of the campus of Harvard University that held an archive of his unpublished papers.