The ever inquisitive Nag on the Lake has a nice vignette about the creative repurposing of the elegant, Victorian girders of the Pancras Gasholder to frame a nice park in London, which reminded me of the Gasometers we’ve encountered reinvented and venues for a wide variety of displays.

Thursday 12 November 2015

gasworks gallery

catagories: 🇬🇧, 💡, architecture, environment, Saxony

Thursday 1 October 2015

the devil and the deep blue sea

If you have not yet treated yourself to the absolutely edifying oblectation of Futility Closet series of podcasts, I strongly recommend you began with their latest instalment on the forgotten story of gentleman merchant raider of World War I, Felix Graf von Luckner. This swash-buckling villain has been overshadowed by other semi-legendary figures of the time—like the Red Baron, but was turned hero for his humanity and persecuting war without causalities. Posing as a Norwegian logging vessel, Luckner’s captained his crew of privateers in a somewhat anchronistic sailing ship called the Seeadler through the supply lines of the Atlantic, confounding materiel delivery and treating his hostages as friends—a sentiment that was reciprocated, but that’s only the barest outline of the tale. It’s definitely worth working backwards as well to catch up on all the engrossing episodes.

If you have not yet treated yourself to the absolutely edifying oblectation of Futility Closet series of podcasts, I strongly recommend you began with their latest instalment on the forgotten story of gentleman merchant raider of World War I, Felix Graf von Luckner. This swash-buckling villain has been overshadowed by other semi-legendary figures of the time—like the Red Baron, but was turned hero for his humanity and persecuting war without causalities. Posing as a Norwegian logging vessel, Luckner’s captained his crew of privateers in a somewhat anchronistic sailing ship called the Seeadler through the supply lines of the Atlantic, confounding materiel delivery and treating his hostages as friends—a sentiment that was reciprocated, but that’s only the barest outline of the tale. It’s definitely worth working backwards as well to catch up on all the engrossing episodes.

Friday 19 June 2015

5x5

straβenverkkehrsordnung: a unique roadway configuration and the technicalities of traffic regulations means that one stop light has been red for three decades in Dresden

four thousand holes in blackburn, lancashire: internet giant is checking computer reading-comprehension with conservative, sensational tabloids

electric babysitter: artist captures images of her children in listless, powerful moments of watching TV

raptor squat: honest-to-goodness zookeepers re-enacting pose from new Jurassic World

Thursday 4 June 2015

present and perdurant

Though modern Greek has adopted a more straightforward term to convey happiness, ευτυχία—just suggesting good works—the classical term Eudæmonia is fortunately still around with all its mysterious and internecine intrigues.

The greatest minds are unable to come to a consensus on what constitutes happiness (or whether that’s even a question worthy of pursuit), but I have to wonder if even the first interlocutors really knew what was meant by Eudæmonia. Semantics are of course important considerations and flourishing or thriving might be a better word than our emotionally-laden happiness—the Romans rendered it as felicitas, who was also sometimes deified, but I don’t believe that any translation could capture the sense of being a role-model compounded with a guardian angel or fairy godmother figure like the original Greek. One achieves happiness, it’s argued, by emulating the example of that demon—dæmons just being spirits, familiars or lesser deities and not diabolical ones. The nature of those qualities and whether there’s some universal imperative are hopeless elusive, though that does not mean we shouldn’t bother. Furthermore, one’s level of bliss can be impacted retroactively should one’s present deportment cause him or her to earn a bad reputation after death.

The greatest minds are unable to come to a consensus on what constitutes happiness (or whether that’s even a question worthy of pursuit), but I have to wonder if even the first interlocutors really knew what was meant by Eudæmonia. Semantics are of course important considerations and flourishing or thriving might be a better word than our emotionally-laden happiness—the Romans rendered it as felicitas, who was also sometimes deified, but I don’t believe that any translation could capture the sense of being a role-model compounded with a guardian angel or fairy godmother figure like the original Greek. One achieves happiness, it’s argued, by emulating the example of that demon—dæmons just being spirits, familiars or lesser deities and not diabolical ones. The nature of those qualities and whether there’s some universal imperative are hopeless elusive, though that does not mean we shouldn’t bother. Furthermore, one’s level of bliss can be impacted retroactively should one’s present deportment cause him or her to earn a bad reputation after death.

Thinking about these rarefied ideas in general and particularly the last bit that invokes the directionality of time makes me turn back to the novel I am currently enjoying, Jo Walton’s absolutely amazing Just City—wherein the goddess Athena gathers the prescribed youth from all ages in order to experimentally create the utopia of Plato’s Republic overseen by those who’ve prayed for wisdom. I wonder if one’s eudæmon isn’t more of a conflicted personality, like shoulder angels. The cover of the Walton’s book, incidentally, focusses in on a particular section of this larger famous fresco by Raphael—showing students engaged on the steps of the Academy below. The different elements and possible perspectives in this work of art makes me think about another of Raphael’s masterpieces, the Sistine Madonna, who’s two puti reflecting upward has become a better known detail. H and I got to see it in its entirety in Dresden once. The aforementioned fresco, however, is out of public view in the papal apartments but I recalled the style and how the tableaux extended beyond the frame, preceding into the background, as the image that was on our ticket stubs from the Vatican Museum—the ephemera buried behind too many layers of our bulletin board to excavate, just now. I don’t believe I am any closer to the being able to articulate what happiness is but do feel I’ve gone on a little trip in time just now myself.

Thinking about these rarefied ideas in general and particularly the last bit that invokes the directionality of time makes me turn back to the novel I am currently enjoying, Jo Walton’s absolutely amazing Just City—wherein the goddess Athena gathers the prescribed youth from all ages in order to experimentally create the utopia of Plato’s Republic overseen by those who’ve prayed for wisdom. I wonder if one’s eudæmon isn’t more of a conflicted personality, like shoulder angels. The cover of the Walton’s book, incidentally, focusses in on a particular section of this larger famous fresco by Raphael—showing students engaged on the steps of the Academy below. The different elements and possible perspectives in this work of art makes me think about another of Raphael’s masterpieces, the Sistine Madonna, who’s two puti reflecting upward has become a better known detail. H and I got to see it in its entirety in Dresden once. The aforementioned fresco, however, is out of public view in the papal apartments but I recalled the style and how the tableaux extended beyond the frame, preceding into the background, as the image that was on our ticket stubs from the Vatican Museum—the ephemera buried behind too many layers of our bulletin board to excavate, just now. I don’t believe I am any closer to the being able to articulate what happiness is but do feel I’ve gone on a little trip in time just now myself.

catagories: 🇬🇷, 🇮🇹, 🧠, language, myth and monsters, philosophy, Saxony, travel, Wikipedia

Friday 29 May 2015

alles gute zum geburtstag!

catagories: 🇩🇪, holidays and observances, Saxony

Monday 11 May 2015

der natur auf der spur oder welcome to the monkey-house

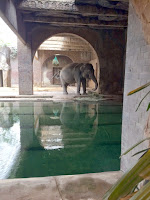

Over the weekend, H and I had the chance to take a safari through the storied and thoroughly progressive zoological gardens of Leipzig, about time too as we have been coming to the city regularly for year now.

Over the weekend, H and I had the chance to take a safari through the storied and thoroughly progressive zoological gardens of Leipzig, about time too as we have been coming to the city regularly for year now.

Founded for the indemnifying of the public in 1878, the menagerie has expanded immensely in the last couple of decades as has the zoo’s mission for conservation and education.

Founded for the indemnifying of the public in 1878, the menagerie has expanded immensely in the last couple of decades as has the zoo’s mission for conservation and education.

There was also expertly and exotically landscaped lagoons of flamingos, an expansive serengeti, a temple for elephants and many other installations (including ones featuring biomes closer to home) with amenities and little intrusion from those who come to gawk.

There was also expertly and exotically landscaped lagoons of flamingos, an expansive serengeti, a temple for elephants and many other installations (including ones featuring biomes closer to home) with amenities and little intrusion from those who come to gawk.  The zoo was no amusement park ride, nor side-show attraction but rather a powerful, interactive lesson in diversity and amazing adaptability of life that really confronts one with the vulnerability of our quirkiest, most-specialised cousins.

The zoo was no amusement park ride, nor side-show attraction but rather a powerful, interactive lesson in diversity and amazing adaptability of life that really confronts one with the vulnerability of our quirkiest, most-specialised cousins. One of the most popular daily soap operas in Germany profiles resident animals and their caretakers and is broadcast from here every afternoon. The whole day was hardly long enough for a proper visit and hope to come back soon to learn more.

One of the most popular daily soap operas in Germany profiles resident animals and their caretakers and is broadcast from here every afternoon. The whole day was hardly long enough for a proper visit and hope to come back soon to learn more.

Tuesday 24 March 2015

rex mundi or spirits in the material world

The massacre of the Cathars in Europe—particularly in their bastions of southern France is not just a historical curiosity, a footnote or something merely comparable with the ongoing plight and persecution of the Yazidi under contemporary righteous bullies and deserves much more of a mention than a few lines sandwiched between the more well-known campaigns of the Children’s Crusades and the Reconquista. What little that is known for certain about the beliefs and traditions of people grouped under the name Cathar, which means pure one but may have been applied in the pejorative sense to a whole spectrum of individuals with unorthodox tenets, is scant and suspect since it was chronicled by those who sought to exterminate heresy in all its forms. A few common accusations of the inquisitors sketches at least a faint outline of the framework of their belief—the dichotomy between the material and spiritual world, which are the handiwork of distinct gods, the former faulty, evil and covetous and the later perfection, goodness and love, and born to the dual nature of mind and body, they believed that they were duty-bound (as reflected by their manner of worship) to try to reconcile this dual-nature through a series of reincarnation until finally pure, having elevated and shed that physical form.

The massacre of the Cathars in Europe—particularly in their bastions of southern France is not just a historical curiosity, a footnote or something merely comparable with the ongoing plight and persecution of the Yazidi under contemporary righteous bullies and deserves much more of a mention than a few lines sandwiched between the more well-known campaigns of the Children’s Crusades and the Reconquista. What little that is known for certain about the beliefs and traditions of people grouped under the name Cathar, which means pure one but may have been applied in the pejorative sense to a whole spectrum of individuals with unorthodox tenets, is scant and suspect since it was chronicled by those who sought to exterminate heresy in all its forms. A few common accusations of the inquisitors sketches at least a faint outline of the framework of their belief—the dichotomy between the material and spiritual world, which are the handiwork of distinct gods, the former faulty, evil and covetous and the later perfection, goodness and love, and born to the dual nature of mind and body, they believed that they were duty-bound (as reflected by their manner of worship) to try to reconcile this dual-nature through a series of reincarnation until finally pure, having elevated and shed that physical form.

For decades, missionaries were sent into the Balkans, where the faith had probably originated, and into parts of southern France and Italy to try to reform the Cathars—but seeing no conversions for all their efforts and with the needed catalyst came in the form of murdered papal delegate, accompanied by Saint Dominic, and perhaps more pointedly, the tacit permission to sack Byzantium, a twenty-year long purge, called the Albigensian Crusade (named for the arch-diocese of Albi, which was in the centre of Cathar country), was launched to rid Languedoc of Cathar influences. Of course, frustrated clerics and nobles welcomed themselves to the spoils of the auto-de-fay. The story of this persecution, however, is an even greater crime than mankind generally unleashes on his own kind in that, like the destruction of Constantinople in terms of learning and culture lost to the world, the region that was home to most of the Cathars prior to the beginning of the thirteenth century, the Aude praire with the cities of Carcassonne, Narbonne, Perpignan, Nîmes, Toulouse and Avignon, was probably the chief contender for the most refined and advanced territory in all of medieval Europe—everything in between Ireland (with its monasteries, which were also irritants for the Church but remote enough to be left alone) and said Constantinople—which now toppled, exposed Europe to incursions from the Mongols and Ottomans.

For decades, missionaries were sent into the Balkans, where the faith had probably originated, and into parts of southern France and Italy to try to reform the Cathars—but seeing no conversions for all their efforts and with the needed catalyst came in the form of murdered papal delegate, accompanied by Saint Dominic, and perhaps more pointedly, the tacit permission to sack Byzantium, a twenty-year long purge, called the Albigensian Crusade (named for the arch-diocese of Albi, which was in the centre of Cathar country), was launched to rid Languedoc of Cathar influences. Of course, frustrated clerics and nobles welcomed themselves to the spoils of the auto-de-fay. The story of this persecution, however, is an even greater crime than mankind generally unleashes on his own kind in that, like the destruction of Constantinople in terms of learning and culture lost to the world, the region that was home to most of the Cathars prior to the beginning of the thirteenth century, the Aude praire with the cities of Carcassonne, Narbonne, Perpignan, Nîmes, Toulouse and Avignon, was probably the chief contender for the most refined and advanced territory in all of medieval Europe—everything in between Ireland (with its monasteries, which were also irritants for the Church but remote enough to be left alone) and said Constantinople—which now toppled, exposed Europe to incursions from the Mongols and Ottomans.Hints of this cultivation remain in the architectural tradition but little else, as the genocide was nearly total. Anecdotally at least, this indiscriminate slaughter was the source of the saying, paraphrased, “Kill ‘em all and let God sort them out.” Caedite eos. Novit enim Dominus qui sunt eius. Pockets endured in the most remote rural areas and Cathar communities were also incorporated into other sects of outliers, the new Protestants and the Moravian (Herrenhuter) of the German woodlands. On a lighter note, happily an international café chain affords us the opportunity to reflect and share our experiences with gnosticism and the Albigensian Crusade by branding the avatar of the dread and almighty Abraxas on all their merchandise.

Monday 2 March 2015

cowboys and indians: sophomoric or dress right dress

Between what has become attested by history as the First and Second Crusade, there were several abortive waves of recruitment, which poor conditions in Europe—including poor harvests, civil unrest and the usual skirmishes between the kingdoms of the realm. Outside of the chief cities of Jerusalem, Haifa, Acre, Jaffa, Tripoli, Antioch and Edessa, control of the Crusader States territory was tenuous at best and quite treacherous for pilgrims or relief- and resupply-convoys. The advent of a novel military, monastic order, the Poor Fellow-Soldiers of Christ and of the Temple of Solomon, the Templars in short-form and followed by the Knights Hospitaller, who could provide armed escourt was a help but their numbers were too disperse to launch coordinated campaigns and besides answered to God and the Church and were not a mercenary shock-force beholden to a local lord, as was the norm for Europe and the Middle East during this time. No ruler, however rich, for the most part had the luxury of maintaining a standing-army in times of (relative) peace and had to raise forces with a call to arms. The Templars and the other orders, in contrast, were constantly training in the art of battle and comprised, along with their Islamic counterpart, the Assassins, the Occident’s first professional fighting-forces. After around five decades of occupation, the County of Edessa was retaken by Islamic forces, under the leadership of Emir Zengi of Mosul, making the Holy Land all but inaccessible overland to Latin Christendom.

Between what has become attested by history as the First and Second Crusade, there were several abortive waves of recruitment, which poor conditions in Europe—including poor harvests, civil unrest and the usual skirmishes between the kingdoms of the realm. Outside of the chief cities of Jerusalem, Haifa, Acre, Jaffa, Tripoli, Antioch and Edessa, control of the Crusader States territory was tenuous at best and quite treacherous for pilgrims or relief- and resupply-convoys. The advent of a novel military, monastic order, the Poor Fellow-Soldiers of Christ and of the Temple of Solomon, the Templars in short-form and followed by the Knights Hospitaller, who could provide armed escourt was a help but their numbers were too disperse to launch coordinated campaigns and besides answered to God and the Church and were not a mercenary shock-force beholden to a local lord, as was the norm for Europe and the Middle East during this time. No ruler, however rich, for the most part had the luxury of maintaining a standing-army in times of (relative) peace and had to raise forces with a call to arms. The Templars and the other orders, in contrast, were constantly training in the art of battle and comprised, along with their Islamic counterpart, the Assassins, the Occident’s first professional fighting-forces. After around five decades of occupation, the County of Edessa was retaken by Islamic forces, under the leadership of Emir Zengi of Mosul, making the Holy Land all but inaccessible overland to Latin Christendom.

Antioch and other strategic lands looked poised to follow handily. Though the climate may not have been organically ripe for such a mobilisation, with a little assistance by another, charismatic papal legate who appealed to the noble sacrifices made by this Greatest Generation of fifty years hence and the mopey guilt of a young king of France for his immortal soul, eager to do penance and only a Crusade might cleanse his conscious. The adolescent king, Louis VII, in a whirlwind of events, had just months before found himself married to the wealthiest and most powerful heiress in the world, Eleanor of Aquitaine, and then with the death of his father, found himself elevated to the throne.

Antioch and other strategic lands looked poised to follow handily. Though the climate may not have been organically ripe for such a mobilisation, with a little assistance by another, charismatic papal legate who appealed to the noble sacrifices made by this Greatest Generation of fifty years hence and the mopey guilt of a young king of France for his immortal soul, eager to do penance and only a Crusade might cleanse his conscious. The adolescent king, Louis VII, in a whirlwind of events, had just months before found himself married to the wealthiest and most powerful heiress in the world, Eleanor of Aquitaine, and then with the death of his father, found himself elevated to the throne.

Being the king in Paris was a titular affair, as unruly landowners, his teenage wife included who controlled the whole of southwestern France, held much more legitimate power than him, and it was on an early mission to quash a rebellion in the Marne, Louis VII discovered that his men had corralled the entire population of an upstart village, Vitry-en-Perthois, into the church and then proceeded to burn it to the ground. This event haunted Louis for his entire life and sought to make amends and was willing to do anything to save his soul from eternal damnation. Having received the urgent pleas for assistance from the Crusader State, a relatively freshly-elected pope, Eugene III, approached his mentor, the monk Bernard of Clairvaux, as Bishop Adémar had done for the First Crusade, to rouse the people of France to action. Regarding his pupil as somewhat of a rustic, a hayseed, Bernard took the matter into his own hands, and just as with the first crusade, there was some mission-creep.

Being the king in Paris was a titular affair, as unruly landowners, his teenage wife included who controlled the whole of southwestern France, held much more legitimate power than him, and it was on an early mission to quash a rebellion in the Marne, Louis VII discovered that his men had corralled the entire population of an upstart village, Vitry-en-Perthois, into the church and then proceeded to burn it to the ground. This event haunted Louis for his entire life and sought to make amends and was willing to do anything to save his soul from eternal damnation. Having received the urgent pleas for assistance from the Crusader State, a relatively freshly-elected pope, Eugene III, approached his mentor, the monk Bernard of Clairvaux, as Bishop Adémar had done for the First Crusade, to rouse the people of France to action. Regarding his pupil as somewhat of a rustic, a hayseed, Bernard took the matter into his own hands, and just as with the first crusade, there was some mission-creep.

Bernard not only made quite an impression on the people of France, he also traveled to Germany, leaving quite a chain of miracles in his wake and sent missives even further afield.

Eleanor of Aquitaine survived her ordeal but the royal union did not, enchanted first by the opulence of Constantinople, which must have made her staid court in Paris seem like an absolute sty, and then entertained by her uncle, Raymond of Poitiers, in Antioch—where Eleanor found herself among compatriots whom spoke her native Langue d’Oc, both of which Louis found infuriating and there was talk that Eleanor’s close relationship with her host and uncle had become too familiar. All of a sudden, Eleanor expressed her wish to renounce the title of Queen of France, and she sued for annulment of her marriage, based on consanguinity, that she and her husband were fourth cousins and consequently had only had female issue. Louis had Eleanor kidnapped and dragged along to Jerusalem. It was a hard slog over treacherous mountains and sea, with the Turkish forces ambushing the Crusaders at every turn.

Eleanor of Aquitaine survived her ordeal but the royal union did not, enchanted first by the opulence of Constantinople, which must have made her staid court in Paris seem like an absolute sty, and then entertained by her uncle, Raymond of Poitiers, in Antioch—where Eleanor found herself among compatriots whom spoke her native Langue d’Oc, both of which Louis found infuriating and there was talk that Eleanor’s close relationship with her host and uncle had become too familiar. All of a sudden, Eleanor expressed her wish to renounce the title of Queen of France, and she sued for annulment of her marriage, based on consanguinity, that she and her husband were fourth cousins and consequently had only had female issue. Louis had Eleanor kidnapped and dragged along to Jerusalem. It was a hard slog over treacherous mountains and sea, with the Turkish forces ambushing the Crusaders at every turn. All the Crusader forces eventually massed in Jerusalem, but as Edessa—the original object of the Kings’ Crusade, although Jerusalem and absolution was Louis’ own goal—bereft of its Christian population, and places of worship was not really worth the effort any longer. Louis was also probably not overly disposed to helping Antioch by securing the principality’s perimeter, what with his wife having been romanced by its ruler. The armies convened at Acre to try to figure out what to do with all this pent up aggression, concluding disastrously to try to take the city of Damascus, the only Muslim city to have negotiated a peace treaty with the Kingdom of Jerusalem and whose failure was obvious from the outset. Like the bickering Louis and Eleanor magnified and reduplicated thousands of times, the coalition under national commands felt betrayed and had even managed to alienate themselves from former allies, split up and departed by sea back to the mainland. Eleanor and Louis took separate ships. Once back on the mainland, Eleanor was granted a divorce and regained her vast land holdings in Aquitaine and Poitiers—and left her daughters in Louis’ custody.

All the Crusader forces eventually massed in Jerusalem, but as Edessa—the original object of the Kings’ Crusade, although Jerusalem and absolution was Louis’ own goal—bereft of its Christian population, and places of worship was not really worth the effort any longer. Louis was also probably not overly disposed to helping Antioch by securing the principality’s perimeter, what with his wife having been romanced by its ruler. The armies convened at Acre to try to figure out what to do with all this pent up aggression, concluding disastrously to try to take the city of Damascus, the only Muslim city to have negotiated a peace treaty with the Kingdom of Jerusalem and whose failure was obvious from the outset. Like the bickering Louis and Eleanor magnified and reduplicated thousands of times, the coalition under national commands felt betrayed and had even managed to alienate themselves from former allies, split up and departed by sea back to the mainland. Eleanor and Louis took separate ships. Once back on the mainland, Eleanor was granted a divorce and regained her vast land holdings in Aquitaine and Poitiers—and left her daughters in Louis’ custody. Shortly afterward, Eleanor began to fancy another relation—Duke Henry of Normandy and Count of Anjou, and following a short courtship, Eleanor and the heir to the British throne married. Upon the death of Henry I and Henry’s older brother Stephen, the young couple became king and queen of England. As happened with Louis’ sin of omission that led to an entire village perishing while locked in a burning church, Henry II allowed his henchmen to get out of control and murder his former chancellor become archbishop of Canterbury, Thomas à Beckett. Henry was devastated, both personally over the death of his friend that he did not prevent and because his popularity plummeted—forever pinning Henry II with the badge of the king who killed an archbishop (the cathedral becoming a pilgrimage destination to rival the popularity of Way of Saint James, Santiago de Compostela), rather than the reformer who helped to rebuild England after successive civil wars and crises of succession.

Shortly afterward, Eleanor began to fancy another relation—Duke Henry of Normandy and Count of Anjou, and following a short courtship, Eleanor and the heir to the British throne married. Upon the death of Henry I and Henry’s older brother Stephen, the young couple became king and queen of England. As happened with Louis’ sin of omission that led to an entire village perishing while locked in a burning church, Henry II allowed his henchmen to get out of control and murder his former chancellor become archbishop of Canterbury, Thomas à Beckett. Henry was devastated, both personally over the death of his friend that he did not prevent and because his popularity plummeted—forever pinning Henry II with the badge of the king who killed an archbishop (the cathedral becoming a pilgrimage destination to rival the popularity of Way of Saint James, Santiago de Compostela), rather than the reformer who helped to rebuild England after successive civil wars and crises of succession. I wonder if Eleanor had that effect on men. The couple had eight children, whom, honestly unruly, Eleanor and ex-husband Louis VII in sort of a cold war with the English king played against Henry II, who in response kept his wife under house-arrest for a the last decade of his life. Eleanor, reaching an advanced age but active until the end, maintained a key role as regent, ruling in her sons’ names while they were away on campaigns, including the wicked and lazy King John (of Robin Hood lore but who really was made to sign the Magna Carta and limit his own power) and Richard Lionheart, who will play a key role in the next Crusade.

Monday 12 January 2015

touchstones oder sonderweg

Democratic reforms elsewhere in Europe—including France, culminated in 1848 in Frankfurt am Main with a Constitutional Convention, which rejected the decimated gerrymandering of the former Empire, from some three-hundred fifty quasi-independent states to a confederation of a mere thirty-seven, as not being representative of the people. This revolution, though uniting and healing and never quite killed, did rather die on the vine, with Prussia and other regional powers tossing out democratic ideals, feeling that they had served their purpose and were in the environment of security and renewed prosperity were dangerous and subversive.

Democratic reforms elsewhere in Europe—including France, culminated in 1848 in Frankfurt am Main with a Constitutional Convention, which rejected the decimated gerrymandering of the former Empire, from some three-hundred fifty quasi-independent states to a confederation of a mere thirty-seven, as not being representative of the people. This revolution, though uniting and healing and never quite killed, did rather die on the vine, with Prussia and other regional powers tossing out democratic ideals, feeling that they had served their purpose and were in the environment of security and renewed prosperity were dangerous and subversive. In the two years, however, that a united and republican Germany prevailed—not to be taken up again until after the defeat and horrors of World War I in the short-lived Weimar Republic—convened under the auspices of the Bauhaus Movement, in an opera house like the Frankfurt summit in a church, a few trappings and symbols that were destined to return were popularised:

the German tri-colour of gold, black and red (supposedly inspired by the uniforms that a group of resistance fighters worn during the Napoleonic Wars) and without the insignia of any particular royal-holding but rather of the people was briefly flown, and the German national anthem was sung. “Deutschland, Deutschland über Alles,” was not a lyric of dominance but rather a plea for an end to Kleinstaaterei and internal division, though now replaced with the excusable and admirable trinity of Einigheit und Recht und Freiheit (Unity, Rule of Law and Freedom) originally extolled in the third verse. These events were not an abortive revolution but rather sentiments that came before their times. One other premature development came about this same year, with social scientists and agitators Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels first publishing a thin pamphlet in Köln called the Manifesto of the Communist Party (Manifest der kommunistischen Partei) which described all of history as class-struggles, but this too garnered little attention at the time.

the German tri-colour of gold, black and red (supposedly inspired by the uniforms that a group of resistance fighters worn during the Napoleonic Wars) and without the insignia of any particular royal-holding but rather of the people was briefly flown, and the German national anthem was sung. “Deutschland, Deutschland über Alles,” was not a lyric of dominance but rather a plea for an end to Kleinstaaterei and internal division, though now replaced with the excusable and admirable trinity of Einigheit und Recht und Freiheit (Unity, Rule of Law and Freedom) originally extolled in the third verse. These events were not an abortive revolution but rather sentiments that came before their times. One other premature development came about this same year, with social scientists and agitators Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels first publishing a thin pamphlet in Köln called the Manifesto of the Communist Party (Manifest der kommunistischen Partei) which described all of history as class-struggles, but this too garnered little attention at the time.

Saturday 10 January 2015

sturm und drang oder elective affinities

Although the land of Alsace had been in possession of the French Empire, annexed from the Holy Roman Empire, for more than a century in this most recent in a long chain of redrawing borders, there still was a large German student population at the illustrious university and the city’s architecture and high spires of its cathedral—though somewhat mistakenly—struck Goethe as quintessentially German but not in the nationalistic sense (there was no Germany, just a loose confederation of city-states, petty kingdoms and imperial monasteries with varying degrees of allegiance to the Emperor) but rather as a community united in language, in the artistic sense as well as the spoken word. Goethe became particularly keen on this notion, drawing from his own childhood experiences being educated with a very liberal curriculum that included the classics and world literature, and finding more and more frustration and dissatisfaction with his own writing projects—as meaning and passion seemed to retreat from his poems (overtures to one young mistress especially) the more he applied himself.

Although the land of Alsace had been in possession of the French Empire, annexed from the Holy Roman Empire, for more than a century in this most recent in a long chain of redrawing borders, there still was a large German student population at the illustrious university and the city’s architecture and high spires of its cathedral—though somewhat mistakenly—struck Goethe as quintessentially German but not in the nationalistic sense (there was no Germany, just a loose confederation of city-states, petty kingdoms and imperial monasteries with varying degrees of allegiance to the Emperor) but rather as a community united in language, in the artistic sense as well as the spoken word. Goethe became particularly keen on this notion, drawing from his own childhood experiences being educated with a very liberal curriculum that included the classics and world literature, and finding more and more frustration and dissatisfaction with his own writing projects—as meaning and passion seemed to retreat from his poems (overtures to one young mistress especially) the more he applied himself.In Strasbourg, Goethe saw his horizons broaden and the literary world unfurled before him when he was introduced to the plays and sonnets of one bard called William Shakespeare, and found in Shakespeare’s free-wheeling and bold manner the conventions that he sought for own prose. Back at the family home, the prodigal son celebrated his first love fest to the Bard and his muse with a “Shakespeare Day” on 14 October with some of his classmates. Goethe’s family saw no harm in their son’s renewed interest in writing, as his marks had improved and would be allowed to open a small practise in first in Frankfurt then in Wetzlar. His career as a lawyer, however, was destined to be a short one—Goethe often courting contempt by demanding clemency for clients and more enlightened, progressive laws. Perhaps sensing that this was the wrong vocation or perhaps because of his moonlighting, Goethe worked extensively on his first novel, The Sorrows of Young Werther (Die Leiden des jungen Werthers)—a semi-autobiographical account of a failed love affair told in correspondence and climaxing in the anti-hero’s suicide. The novel was an instant sensation and helped to propel, just as Shakespeare had done for English, German into the pantheon of literary and scholarly languages. Though not the stylings of emo or goth, young men were dressing as Werther (Werther-Fieber it was called) and tragically, there were some urged to the same ending after reading the book—and not just in Germany but all over. Fearing the dangerous influence that this potentially subversive work might have if the international celebrity might be allowed to spread unabated, a writer and publisher called Christoph Friedrich Nikolai from Frankfurt an der Oder, in central Prussia, went so far as to give the story a Hollywood ending, under the title “The Joys of Young Werther.”

Napoleon was a committed fan as were many others. The political discontinuity that charaterised the Holy Roman Empire was a grave subject of consternation to outsiders, who lived under more centralised governments, but as the city-states of an equally fractious Italy during the Renaissance encouraged the arts through patronage—every little lord wanting to retain pet talent, the same sort of arrangement could be fostered in Germany, and Goethe’s book caught the attention of one young heir-apparent to the small but grand duchy of Saxe-Weimar-Eisenach. This enlightened ruler ennobled Goethe—putting the von in his name—and kept him on in Weimar for the rest of his life.

Napoleon was a committed fan as were many others. The political discontinuity that charaterised the Holy Roman Empire was a grave subject of consternation to outsiders, who lived under more centralised governments, but as the city-states of an equally fractious Italy during the Renaissance encouraged the arts through patronage—every little lord wanting to retain pet talent, the same sort of arrangement could be fostered in Germany, and Goethe’s book caught the attention of one young heir-apparent to the small but grand duchy of Saxe-Weimar-Eisenach. This enlightened ruler ennobled Goethe—putting the von in his name—and kept him on in Weimar for the rest of his life. The young duke was of the same line who had two-hundred fifty years earlier had the courage and the wherewithal to provide sanctuary in the Wartburg by Eisenach to another controversial figure, Martin Luther—whereas in a more unified society with no place to seek refuge, like France or England, the Reformer would have been burnt at the stake for heresy. Goethe held a number of royal offices through his career, which afforded him travel on diplomatic missions throughout Europe and experiences Goethe could not have otherwise obtained, meeting many other contemporary luminaries—while not infringing on his writing and scientific studies. Goethe was deeply interested in all facets of existence and was absolutely prodigious in many fields, having amassed the largest mineral collections in Europe, published several seminal treatises on botany, optics and anatomy (which included some inspiring observations that Charles Darwin took to heart), and meteorology (researching the forecasting nature of barometric pressure) among others.

The young duke was of the same line who had two-hundred fifty years earlier had the courage and the wherewithal to provide sanctuary in the Wartburg by Eisenach to another controversial figure, Martin Luther—whereas in a more unified society with no place to seek refuge, like France or England, the Reformer would have been burnt at the stake for heresy. Goethe held a number of royal offices through his career, which afforded him travel on diplomatic missions throughout Europe and experiences Goethe could not have otherwise obtained, meeting many other contemporary luminaries—while not infringing on his writing and scientific studies. Goethe was deeply interested in all facets of existence and was absolutely prodigious in many fields, having amassed the largest mineral collections in Europe, published several seminal treatises on botany, optics and anatomy (which included some inspiring observations that Charles Darwin took to heart), and meteorology (researching the forecasting nature of barometric pressure) among others.

Friday 2 January 2015

broadsheet

This past year was certainly a banner one for anniversaries and centenaries marked the world over, and it seems as if the trend is hardly escapable since we’re survivors of history’s dreadful-excellent heap of memory.

It is a good thing surely not to forget to celebrate what we’ve achieved and overcome but this whole movement to propagrandise and make, especially a century’s passing, a moment of national pride and a rallying-cause happened in 1617—one hundred years after reformer Martin Luther famously nailed his Ninety-Five Theses to the door of Wittenberger Dom and sparked the era of Protestantism, masterfully captured in this poster with quite a bit of allegory to study, like a political cartoon. Of course, this stand is celebrated every year—peacefully and surely Luther does not endorse the use of his likeness for this campaign message, on 1 November, but apolitically. Mass distribution of this broadsheet—and Luther’s Bible, were made possible by newly introduced printing technologies and the Princes of Prussia certainly were not going to let the date go by without some manipulative media. Clashing forces of the Lutherans and the counter-Reformist Catholic lands in a fractured Holy Roman Empire quickly escalated—especially with sentiments fueled on both sides by caricature and fear-mongering, and led to the Thirty Years War, which was one of the darkest and bloodiest wars of European history Christian sectarianism. I hope that we don’t need our memory jarred with new violence for old.

It is a good thing surely not to forget to celebrate what we’ve achieved and overcome but this whole movement to propagrandise and make, especially a century’s passing, a moment of national pride and a rallying-cause happened in 1617—one hundred years after reformer Martin Luther famously nailed his Ninety-Five Theses to the door of Wittenberger Dom and sparked the era of Protestantism, masterfully captured in this poster with quite a bit of allegory to study, like a political cartoon. Of course, this stand is celebrated every year—peacefully and surely Luther does not endorse the use of his likeness for this campaign message, on 1 November, but apolitically. Mass distribution of this broadsheet—and Luther’s Bible, were made possible by newly introduced printing technologies and the Princes of Prussia certainly were not going to let the date go by without some manipulative media. Clashing forces of the Lutherans and the counter-Reformist Catholic lands in a fractured Holy Roman Empire quickly escalated—especially with sentiments fueled on both sides by caricature and fear-mongering, and led to the Thirty Years War, which was one of the darkest and bloodiest wars of European history Christian sectarianism. I hope that we don’t need our memory jarred with new violence for old.

catagories: 🌍, 🧠, foreign policy, religion, revolution, Saxony, Thüringen

Thursday 18 December 2014

like a picture print from currier and ives

As the fourth Advent comes rolling in, here are a few scenes from Christmas markets in Wiesbaden, Leipzig and Erfurt to celebrate the season. PfRC wishes you all good cheer, be kind to one another, and thanks for visiting.

catagories: Hessen, holidays and observances, networking and blogging, Saxony, Thüringen

Monday 15 December 2014

perfidy

Patterned after the Monday Demonstrations that brought down the regime of East Germany, the PEGIDA (Patriotsche Europäer gegen die Islamisierung des Abendlandes—Patriotic Europeans Against the Islamisation of the Occident, the West) marches are growing in numbers and frequency but are still rivaled by counter demonstrations. The German government, rightly, condemns the movement as racist and xenophobic. Trying to lend a legitimising air to thuggish and insular attitudes that were first championed by football hooligans (at least in costume, one has a better idea of what one is up against), these marches are hardly proving to be a civil way to channel frustrations or fears, what with public opinion splintered, calls that immigrants refrain from conversing in their native language at home and arson-attacks on refugee housing. I believe there are two very different things occurring here and bigots always capitalize on this confusion: immigration politics are not threatening to displace one’s culture and the level of interaction that all of these marchers have had with any form of Islam is limited to seeing families out in public and making assumptions, which does not exactly equate to an agenda of systematically imposing one’s way of life and values. Petitioning one’s government over real concerns for reform is one thing and resorting to violence and fear-mongering is quite another. Ideology and identity are not the same thing—but both run both ways.

Patterned after the Monday Demonstrations that brought down the regime of East Germany, the PEGIDA (Patriotsche Europäer gegen die Islamisierung des Abendlandes—Patriotic Europeans Against the Islamisation of the Occident, the West) marches are growing in numbers and frequency but are still rivaled by counter demonstrations. The German government, rightly, condemns the movement as racist and xenophobic. Trying to lend a legitimising air to thuggish and insular attitudes that were first championed by football hooligans (at least in costume, one has a better idea of what one is up against), these marches are hardly proving to be a civil way to channel frustrations or fears, what with public opinion splintered, calls that immigrants refrain from conversing in their native language at home and arson-attacks on refugee housing. I believe there are two very different things occurring here and bigots always capitalize on this confusion: immigration politics are not threatening to displace one’s culture and the level of interaction that all of these marchers have had with any form of Islam is limited to seeing families out in public and making assumptions, which does not exactly equate to an agenda of systematically imposing one’s way of life and values. Petitioning one’s government over real concerns for reform is one thing and resorting to violence and fear-mongering is quite another. Ideology and identity are not the same thing—but both run both ways.

Friday 14 November 2014

vocabulary spurt or the pump don’t work ‘cause vandals broke the handle

I have been thoroughly enjoying a brilliant new series of podcasts on the development of English as the global lingua franca that examines its roots from proto Indo-European origins, migrations, cultural exchange and dissemination. There’s a lot of engrossing history presented through curious etymologies, and although I have heard of some of these noble linguistic lineages before there’s no exhausting the emerging connections. The thrust of the series is of course the particular dialect of the Anglo-Saxons that has survived, with much outside influences, borrowings and impositions, to the modern day—but there are also many worthy tangents explored.

The Angles (which means crook, like an angle or a hook used in fishing and preserved in the German word Angeln for that act, and is in reference to the shape of the Danish pennisula of Jutland, their homeland, and gives us the name East Anglia and England), later merging with the Saxons (meaning Swordmen and source of the designations Essex, Wessex and Sussex for the kingdoms of the East, West and South Saxons), moved into England from the German coast region of the North Sea once Rome had retreated from the island. The fleeing romanized Britons lent their name to the province of Brittany just across the English Channel, Mor Breizh or La Manche. The tribes that gives Germany the place-names of Bavaria and Franconia—and originally Bohemia and France from whence they came, were Celtic people. With the later Norman Invasion of England (the Normans being Norse transplants themselves), the French language had a major impact on English vocabulary, with the name of the Frankish tribe itself having a rather stimulating history and legacy: some linguists postulate that this Gallic group was called “free” because of early treaties with the Romans that formed a confederation that made certain allowances for home-rule and in exchange for defending the Empire’s frontier, were free to cross into Roman territory, and by way of French influences, English has the word frank (freimütig), for being open or just blunt, franchise (generally, a right or privilege or the right to sell under a parent label), disenfranchised (having those rights sidelined), and what’s called franking (Frankatur) privileges, the right to print postage stamps. The Chatti tribe gave the federal state of Hessen its name, following the sound shifts of Grimm’s Law. The Alemanni settled along the Main and Rhine and their territory stretched from Alsace to Switzerland; the tribe was eventually overtaken and assumed a Frankish identity but the name, “all men”—probably a catch-all name for the various clans in this broad area, is retained in the toponym of Germany in many of the Romance languages. Even if one calls Deutschland Germany, one might still know how to allemande right and left (the Germans supposedly did this particular move) at the ball or square dance.

A league of tribes that ganged up against the Romans when they were already going down was called the Marcomanni, and it is from the alliance of these “border men” that we have the word for march (Mark) in the sense of a frontier and the title of Marquis (Margrave). Other Germanic tribes, that went east and south respectively, give us the name for the Burgundy region of France and the Lombardy region of Italy. One common Lombard first name was Irmen which became Amerigo once Italian speech returned and it was one certain cartographer by the name of Vespucci who demonstrated to the world that Christopher Columbus had indeed arrived in the Caribbean and not the East Indies as the explorer insisted and for whom two continents are named. Academics have the works of Ancient Roman historian Gaius Cornelius Tacitus—where the adjectives tacit and taciturn for his compact and direct writing style—for much of this source information, and aside from Julius Caesar’s personal accounts, there is very little other documentation. Consequently, every sentence has been poured over and dissected over the last six hundred years, after the sole surviving copy was discovered in the Abbey of Bad Hersfeld, of this short ethnograph. And whereas, certain comments reflective one person’s opinion or generalisation might be dismissed or taken with a grain of salt within a larger work (though this happens with the Bible and company too), selective-readers highlighted passages that unfortunately praised the Germanic race as being the purest and the noblest one amongst these savages and turned these words in dangerous directions.

A league of tribes that ganged up against the Romans when they were already going down was called the Marcomanni, and it is from the alliance of these “border men” that we have the word for march (Mark) in the sense of a frontier and the title of Marquis (Margrave). Other Germanic tribes, that went east and south respectively, give us the name for the Burgundy region of France and the Lombardy region of Italy. One common Lombard first name was Irmen which became Amerigo once Italian speech returned and it was one certain cartographer by the name of Vespucci who demonstrated to the world that Christopher Columbus had indeed arrived in the Caribbean and not the East Indies as the explorer insisted and for whom two continents are named. Academics have the works of Ancient Roman historian Gaius Cornelius Tacitus—where the adjectives tacit and taciturn for his compact and direct writing style—for much of this source information, and aside from Julius Caesar’s personal accounts, there is very little other documentation. Consequently, every sentence has been poured over and dissected over the last six hundred years, after the sole surviving copy was discovered in the Abbey of Bad Hersfeld, of this short ethnograph. And whereas, certain comments reflective one person’s opinion or generalisation might be dismissed or taken with a grain of salt within a larger work (though this happens with the Bible and company too), selective-readers highlighted passages that unfortunately praised the Germanic race as being the purest and the noblest one amongst these savages and turned these words in dangerous directions.

Monday 29 September 2014

leipziger freiheit oder wir sind das volk

Other urban centres—perhaps most famously Munich, have neighbourhoods, avenues called Freiheit—what with the Münchener Freiheit though that was something I always understood as Freitzeit, a boulevard to stroll for one’s own leisurely pursuits. The Leipziger Freitheit does not seem to be a particular locale but rather a perennial celebration of the seminal and decisive night of 9 October 1989 (DE/EN), the fortieth anniversary of the establishment of the Deutsche Demokratic Republik, the DDR.

Other urban centres—perhaps most famously Munich, have neighbourhoods, avenues called Freiheit—what with the Münchener Freiheit though that was something I always understood as Freitzeit, a boulevard to stroll for one’s own leisurely pursuits. The Leipziger Freitheit does not seem to be a particular locale but rather a perennial celebration of the seminal and decisive night of 9 October 1989 (DE/EN), the fortieth anniversary of the establishment of the Deutsche Demokratic Republik, the DDR.

Scant weeks after the first Montagsdemo, held under the auspices and protection of the Nikolaikirche pastors, keeping the assembly peaceful no matter what the authorities tried was presented as something sacrosanct. Security forces were girded for anything, except the prayers for peace and candle-lit vigil of some seventy-thousand souls marching en masse. There was no violent opposition—and it seems that protesters and the police became united in this pact. Numbers grew in the following weeks and the movement spread to other cities, encouraged by their own success and extensive coverage by the Western press.

Scant weeks after the first Montagsdemo, held under the auspices and protection of the Nikolaikirche pastors, keeping the assembly peaceful no matter what the authorities tried was presented as something sacrosanct. Security forces were girded for anything, except the prayers for peace and candle-lit vigil of some seventy-thousand souls marching en masse. There was no violent opposition—and it seems that protesters and the police became united in this pact. Numbers grew in the following weeks and the movement spread to other cities, encouraged by their own success and extensive coverage by the Western press.

A month later, the Wall came down and ushered the fall of the regime and German reunification, brought about by the convictions and contagious bravery of the people. Leipzig has been honouring this day—and not just for that quarter of a century that has passed, and includes many stations for reflection with vistas over a city illuminated for the occasion.

A month later, the Wall came down and ushered the fall of the regime and German reunification, brought about by the convictions and contagious bravery of the people. Leipzig has been honouring this day—and not just for that quarter of a century that has passed, and includes many stations for reflection with vistas over a city illuminated for the occasion.

The hopeful occasion of the Mauerfall is not remembered, however, on the exact date because of the coincidence of the Schicksalstag, the ninth of November already time-stamped with the abdication of the monarchy near the conclusion of World War I, the coup of Hitler and Kristallnacht and seeming hardly an auspicious day for unity.

The hopeful occasion of the Mauerfall is not remembered, however, on the exact date because of the coincidence of the Schicksalstag, the ninth of November already time-stamped with the abdication of the monarchy near the conclusion of World War I, the coup of Hitler and Kristallnacht and seeming hardly an auspicious day for unity.

catagories: 🇩🇪, religion, revolution, Saxony

Wednesday 9 July 2014

montagsdemo oder wir sind das volk

Though never claiming to be the moral successor to the Montagsdemonstrationen, those peaceful rallies that took place in the late eighties in the public square of the Nikolaikirche in Leipzig, spreading to other cities, protesting the ruling party in East Germany and instrumental in making imminent the reunification, the German press is drawing parallels to a movement began this Spring in Hamburg called Vigils for Peace (Mahnwachen für den Frieden).

catagories: 🇩🇪, 💱, 🥸, foreign policy, revolution, Saxony, Wikipedia

Friday 11 April 2014

pelagic or teuthology

True to the mission and cutting the figue of a Jules Verne character, the voyage rounded the southern cape of Africa and made calls in the South Seas before heading into the subantarctic (below/above) region. Collection efforts were difficult, as many of the strange and never before seen monstrosities harvested disintegrated due to having adapted to the great pressures of the deep, and most samples, like the anglerfish, with its lantern and gaping maw, defied study and classification for years, unobserved in their native environment. Chun, however, does have several new creatures credited to his name, including the vampire squid (from Hell), so called for its black cloak that draped its tentacles, arrayed with spines—and outfitted with night-lights.

True to the mission and cutting the figue of a Jules Verne character, the voyage rounded the southern cape of Africa and made calls in the South Seas before heading into the subantarctic (below/above) region. Collection efforts were difficult, as many of the strange and never before seen monstrosities harvested disintegrated due to having adapted to the great pressures of the deep, and most samples, like the anglerfish, with its lantern and gaping maw, defied study and classification for years, unobserved in their native environment. Chun, however, does have several new creatures credited to his name, including the vampire squid (from Hell), so called for its black cloak that draped its tentacles, arrayed with spines—and outfitted with night-lights.

catagories: 🇩🇪, 📚, 🦑, environment, Saxony

Tuesday 18 March 2014

merkmale

H and I had the chance to re-visit the site in the north of the City of Leipzig, dedicated to the memory of the fallen German and Russian troops who withstood Napoleon's advance on this front and ultimately precipitated his surrender and defeat, after managing to realign and re-distribute much of Europe in a manner that survived his rampage.

H and I had the chance to re-visit the site in the north of the City of Leipzig, dedicated to the memory of the fallen German and Russian troops who withstood Napoleon's advance on this front and ultimately precipitated his surrender and defeat, after managing to realign and re-distribute much of Europe in a manner that survived his rampage. Partnerships of convenience, long-lasting alliances and a much poorer Church emerged from the turmoil. Das Völkerschlachtdenkmal (the monument for the Battle of the Nations) was completed in its unique and defining neo-classical, betraying influences from the Meso-Americans and the Ancient Egyptians and previsioning the Art Déco (Jugendstil) movement, in 1913 for the one-hundredth anniversary of the decisive campaign and underwent extensive restoration of its interior crypt during the past few years for its centennial, honouring the anniversary of the battle this past October.

Partnerships of convenience, long-lasting alliances and a much poorer Church emerged from the turmoil. Das Völkerschlachtdenkmal (the monument for the Battle of the Nations) was completed in its unique and defining neo-classical, betraying influences from the Meso-Americans and the Ancient Egyptians and previsioning the Art Déco (Jugendstil) movement, in 1913 for the one-hundredth anniversary of the decisive campaign and underwent extensive restoration of its interior crypt during the past few years for its centennial, honouring the anniversary of the battle this past October. We were able to see the halls and galleries, a clime of some five-hundred steps (with a lift too but some chambers, like the ancient ziggurats it borrows from, could only be reached through a labyrinth of stairwells that sometimes had one ascending through the colossal statues.

We were able to see the halls and galleries, a clime of some five-hundred steps (with a lift too but some chambers, like the ancient ziggurats it borrows from, could only be reached through a labyrinth of stairwells that sometimes had one ascending through the colossal statues.The monument was misused at times as a symbol of German mysticism and exceptionalism, like the Barbarossa monument commissioned by the self-same German emperor, Kaiser Wilhelm, that sought to strengthen ties among a disparate assemblage of former petty kingdoms as the German Empire, and its East German caretakers proposed at one time to tear it down. I am glad that they didn't and consistently appreciate the charge of a curator.

An inverted bee-hive spiraled high above. No doubt that the crypt is sacred ground and one cannot forget, even when awing at the scale as a tourists, but it was a strange feeling how the experience was reminiscent of Scooby-Doo forensics or the archetype for the staging of an installment of Star-Gate, Riddick and any given action-adventure experience—without being too sacrilegious.

catagories: 🎓, 🎬, 📺, antiques, holidays and observances, revolution, Saxony, travel