The ever-inquiring Nag on the Lake introduces a fascinating sociological phenomenon captured in the ephemera collected by poet and reformer Langston Hughes—intrigued by the little rhyming couplets on the header of invite cards, Hughes amassed quite a number of them when he first came to Harlem in the mid-1950s, that document the plight that black tenents faced in New York City from the 1920s onwards. Low wages combined with price gouging in certain boroughs meant that renters often needed to resort to creative measures (crowd-funding, I guess we would call it today) in order to meet monthly obligations. Many apartments opened up for house parties—which for a nominal entrance fee (refreshments not included), neighbours were treated to a night of music, dancing, card playing and general merry making. Proceeds helped the tenants to bridge the shortfall. Those invitations that Hughes held on to are housed in a special collection at the library of Yale University.

The ever-inquiring Nag on the Lake introduces a fascinating sociological phenomenon captured in the ephemera collected by poet and reformer Langston Hughes—intrigued by the little rhyming couplets on the header of invite cards, Hughes amassed quite a number of them when he first came to Harlem in the mid-1950s, that document the plight that black tenents faced in New York City from the 1920s onwards. Low wages combined with price gouging in certain boroughs meant that renters often needed to resort to creative measures (crowd-funding, I guess we would call it today) in order to meet monthly obligations. Many apartments opened up for house parties—which for a nominal entrance fee (refreshments not included), neighbours were treated to a night of music, dancing, card playing and general merry making. Proceeds helped the tenants to bridge the shortfall. Those invitations that Hughes held on to are housed in a special collection at the library of Yale University.

Sunday 16 August 2015

an evening’s entertainment or byob

Saturday 15 August 2015

her father beat the system by moving bricks to brixton

Hearing news of small-batch artisanal money being minted not to be collectible (while it surely is for a chance to get a Bowie or a Gromit back in change) but to be exchanged for goods and services on a very local level and to supplement the more widely acknowledged legal tender—at parity, it made me think of how for all the woes of globalisation, the phenomenon of hegemony, integration and degredation of native traditions and customs, it does also contain its own antithesis. The anti-globalisation movement is a global one itself and can, especially now thanks to the availability and access of communication, harness some of the same driving factors. Coordinating protests and fund-raisers worldwide among kindred strangers is probably the most apparent example, but evidence of the upside to globalisation is also found in these handsomely crafted bills, the organic and slow food movement, urban victory gardens, seeking out farmers’ markets and locally produced goods, and the increasing number of participants in the so called sharing economy.

Hearing news of small-batch artisanal money being minted not to be collectible (while it surely is for a chance to get a Bowie or a Gromit back in change) but to be exchanged for goods and services on a very local level and to supplement the more widely acknowledged legal tender—at parity, it made me think of how for all the woes of globalisation, the phenomenon of hegemony, integration and degredation of native traditions and customs, it does also contain its own antithesis. The anti-globalisation movement is a global one itself and can, especially now thanks to the availability and access of communication, harness some of the same driving factors. Coordinating protests and fund-raisers worldwide among kindred strangers is probably the most apparent example, but evidence of the upside to globalisation is also found in these handsomely crafted bills, the organic and slow food movement, urban victory gardens, seeking out farmers’ markets and locally produced goods, and the increasing number of participants in the so called sharing economy.

rapture-ready or recursive self-improvement

In the labour market, the concerns about mass redundancy due to advances in robotics is undeniable and computing has gotten quite good at putting on at least a friendly persona, a clever mask for its subroutines that make it possible for the user (client) to engage with it. Maybe humanity’s enduring and abiding mystery is a bit of a conceit itself, and surely the spark of conscious, self-awareness is dulled some if it only amounts to a convincing though banal chat with an automated customer service telephone tree, judged effective if the result is customer satisfaction.

catagories: 💭, 🤖, 🧠, labour, religion, revolution, technology and innovation

5x5

pastafarian: avatar of the divine flying spaghetti monster spotted underseas

umbrella corporation: a web search engine redefines it corporate profile

hall-tree and hutch: Dangerous Minds explores how sci-fi films require long, branching corridors

fun house: revisiting Lucas Samaras’ 1966 mirrored room installation

baumbastik: a visit to the small Alpine village of Neuschönau and the world’s longest tree-top trail

catagories: 🇬🇷, 🌱, 🎬, Bavaria, myth and monsters, networking and blogging, religion

Thursday 13 August 2015

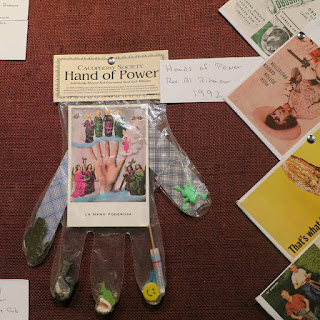

hand of glory

With the collapse of the banking system in Greece, a threatened haircut for private accounts and even the strict rationing of access to money, much of the affected population is understandably still wary of entrusting their wealth to any such institution. This lack of confidence and the physical lack of a safe place to park one’s money—the tycoons and magnates can be more resourceful and liquid, as the magnificent BLDGBlog inspects has led many stashing their cash and valuables under the mattress, and burglars are keenly aware of this shift. Meanwhile, residents are resorting to creative methods of do-it-yourself security-measures in order to stave off or at least discourage break-ins.

Wednesday 12 August 2015

unit of account

After all the concerted efforts to take the wind out of the sails of the various movements that called for fundamental economic reform and the overhaul of usurious and predatory lending practises by shaming, as it were, the indebted with some kind of defective moral flagrancy and inability to curb one’s own spending habits—invoking the osmosis of trickle-down and sop-it-up finances, it strikes me as odd and ironic that this time out of any is called forth as a uniquely disparaging hardship. Invoking the historic notion of jubilee, debt-forgiveness, only illustrates—to my mind, that this problem has visited humanity many times before and modern times is inviting another great reckoning. The popular and somewhat intuitive account for the situation that we all recognise is that barter and trade led to the gradual invention of representative, fiat money as a unit of account and a store of wealth and then to the idea of credit and debt as a sort of virtual currency. And while such a progression seems plausible, I do not think we would have bounded our self-appraisals—the value of our civility to others or even placed a bounty on our not forcibly occupying the lands of another down to something of finite, quantifiable worth.

Plus the ethnographical evidence over an society ever taking the leap to bargaining one cow for a coin redeemable for fifty hens, an acre of pasturage or some repairs to one’s hearth and home as a matter of course is sorely absent and there was no such model economy, as far as we know. With the advent of monetary vehicles, such exchanges were reserved for settling a peace or arranging a proper dowry and union between families and gift-giving persisted on the intimate level—reciprocation and something owed being implicit although returning something of equal esteem would have been regarded, across all cultures, as an insult and as sign of settling accounts and wanting nothing more to do with the relationship. It seems that the progression is reversed and our self-worth looms just as large—only that just a select few—the one percent, have the luxury of creating wealth out of abstractions. From little to nothing, infinite graces can be tapped and flooded, like the familiar parable of the tulip craze that caused the first stock market implosion or the selling of indulgences by the Catholic Church. Imaginative inflation is surely tethered to obligations rather than the accounting sleight of hand, compulsion and exploitation that buoy up the system. Debt and credit is mutually antagonising and though banksters and their ilk are hardly afforded a kindness, there is only a fast-drying well of sympathy for those on the receiving end of the ledger. Those who would dismiss the suffering of those reduced to poverty and desperation, the Greeks and the migrants that would pull everything asunder like their homelands, as a character defect, are themselves overestimating their obedience and abeyance, as it’s only a vanishing difference of a few tenuous degrees that’s purchased that security—albeit a false and vulnerable one. I would wager that many individuals crushed by debts—even many beaten down by inherited ones and knowing no other condition, would place a far higher price on regaining credibility and thriving than those who’ve merely managed to keep up with payments and appeasing one’s own creditors—which doesn’t seem like a very heroic moral high-ground after all.

Plus the ethnographical evidence over an society ever taking the leap to bargaining one cow for a coin redeemable for fifty hens, an acre of pasturage or some repairs to one’s hearth and home as a matter of course is sorely absent and there was no such model economy, as far as we know. With the advent of monetary vehicles, such exchanges were reserved for settling a peace or arranging a proper dowry and union between families and gift-giving persisted on the intimate level—reciprocation and something owed being implicit although returning something of equal esteem would have been regarded, across all cultures, as an insult and as sign of settling accounts and wanting nothing more to do with the relationship. It seems that the progression is reversed and our self-worth looms just as large—only that just a select few—the one percent, have the luxury of creating wealth out of abstractions. From little to nothing, infinite graces can be tapped and flooded, like the familiar parable of the tulip craze that caused the first stock market implosion or the selling of indulgences by the Catholic Church. Imaginative inflation is surely tethered to obligations rather than the accounting sleight of hand, compulsion and exploitation that buoy up the system. Debt and credit is mutually antagonising and though banksters and their ilk are hardly afforded a kindness, there is only a fast-drying well of sympathy for those on the receiving end of the ledger. Those who would dismiss the suffering of those reduced to poverty and desperation, the Greeks and the migrants that would pull everything asunder like their homelands, as a character defect, are themselves overestimating their obedience and abeyance, as it’s only a vanishing difference of a few tenuous degrees that’s purchased that security—albeit a false and vulnerable one. I would wager that many individuals crushed by debts—even many beaten down by inherited ones and knowing no other condition, would place a far higher price on regaining credibility and thriving than those who’ve merely managed to keep up with payments and appeasing one’s own creditors—which doesn’t seem like a very heroic moral high-ground after all.

catagories: 🎓, 💱, 🧠, revolution, Wikipedia

Tuesday 11 August 2015

awimbawe

Learning the other day that the coastal west African nation of Sierra Leone was so named by Portuguese explorers for how its promontory mountain range looked from the sea like a sleeping lion, I was struck about how little I gave much of a thought to the vast and variegated continent. Whereas the doo-wop song was originally a Zulu piece composed in South Africa, whereas I thought the name was a colour like Burnt Sienna, whereas I feel confident that I am not alone in this omission, and whereas I reserved a bit of a purchase on the region by knowing before all the dread news of refugees and communicable disease and blood diamonds that Liberia had a special relationship with the United States by having formed the vague idea that it was somehow founded by freed slaves, I suppose that most people out of Africa regard it as some sort of terrible incubator of the above ills.