Though perhaps not presented in the most rigorous format, Neatoramanaut Rob Manuel does offer a rather compelling and intuitive argument regarding the strictures of time-travel—wherein a back- to-the-future scenario plays out more like being visited by the Ghost of Christmas Past with one being unable to interact or change history in any way.

Thursday 22 October 2015

temporal excursions

catagories: 🎓, philosophy, Wikipedia

Sunday 30 August 2015

dodona and di-oscuri

In one of its latest acquisition released for all, the Public Domain Review presents the 1898 illustrated ethnographical exposition on bird-watching in the Bird Gods by Charles de Kay with decorations by George Wharton Edwards. The book opens with a strong injunction against those who’d seek to preen their own image with furs, skins, plumage and big-game trophies, written at a time just after the herds of buffalo were wiped out in North America and about a decade before the passenger pigeon went extinct and goes on to address the cultural and religious connotations attributed to auguries in action and in their natural habitat.

catagories: 🌍, 📚, 🦢, 🧠, antiques, environment, language, myth and monsters, philosophy, religion

Sunday 26 July 2015

cognitive dissonance

By way of a book review that seeks to make the superficially blithe, a link taken for granted really, connection between our emotions and our physical well-being and resilience—these all being popular concepts that are well rooted in modern thinking—the brilliant Maria Popova of Brain Pickings delivers a surprising historical context and development that demonstrates that the relationship is not a straightforward one and not without coups and reversals of fortune.

catagories: ⚕️, 🎓, 📚, 🧠, philosophy

Monday 20 July 2015

two hours of pushing broom…king of the grove

I have just started essaying the massive tome (the one volume, abridged paperback version) by the influential Scottish anthropologist Sir James Frazer. This ethnographic undertaking had its first best-selling runs around the turn of the past century and was absolutely devoured by scholastics and the reading public. Modern criticism is mostly directed at what strikes the politically-correct attuned ear as chauvinistic and racist and very much dated, and while contemporaries did wonder that Frazer himself was not as savage (or more so) as the primitives he studied in expounding such a monumental work premised on his own ignorance and confusion (the origins of the cycle of death and rebirth and the metaphoric rituals that have arisen that seem to defy explanation).

In Frazer’s own time, however, his work was most controversial in that Christianity’s customs were not spared from the rigourous analysis of how magical thinking creates totem and taboo and progresses onto religion. Subsequent editions of the Golden Bough, referring to the votive branch that gained Æneas entry to the Underworld and reminds me of the later parallel occurrence when Henry II (Henry Plantagenet, the Sprig-Bearer—specifically of a hedge called broom that was cultivated to form the enclosures of landholdings and a nickname that came before this encounter) of England and Normandy met with Philip II of France—under a elm tree near the border town of Gisors, between the kingdoms—and violently fell the innocent tree after their failed embassy (perhaps to negotiate a peace-settlement or as some imaginatively suggest the schism among the Western Christian Military Orders), tended to not subject native religion and customs to the same treatment—although it was clearly superfluous at this point since Frazer had already made his point. As I said, I am just getting started and it is a very dense work but I am already struck by the numerous lucid examples, which I think was a time for privileged witness before war and industry wholly swept away native superstitions, and categorisations of magical thinking and had never before appreciated how homeopathy—whether charms, potions or medicine, is based on the principle—misguided belief that ought to be dispelled, according to Frazer, that like engenders or attracts like. The Golden Bough is pretty dismissive of such recourse, no matter how strongly ingrained but is not an exposition on other merits over mechanisms and relations, and really leaves no room for alibis for practitioners other than medicine men. It’s slow-going, but I am excited to see how the argument progresses and to see whether the self-censorship was a faithful omission.

In Frazer’s own time, however, his work was most controversial in that Christianity’s customs were not spared from the rigourous analysis of how magical thinking creates totem and taboo and progresses onto religion. Subsequent editions of the Golden Bough, referring to the votive branch that gained Æneas entry to the Underworld and reminds me of the later parallel occurrence when Henry II (Henry Plantagenet, the Sprig-Bearer—specifically of a hedge called broom that was cultivated to form the enclosures of landholdings and a nickname that came before this encounter) of England and Normandy met with Philip II of France—under a elm tree near the border town of Gisors, between the kingdoms—and violently fell the innocent tree after their failed embassy (perhaps to negotiate a peace-settlement or as some imaginatively suggest the schism among the Western Christian Military Orders), tended to not subject native religion and customs to the same treatment—although it was clearly superfluous at this point since Frazer had already made his point. As I said, I am just getting started and it is a very dense work but I am already struck by the numerous lucid examples, which I think was a time for privileged witness before war and industry wholly swept away native superstitions, and categorisations of magical thinking and had never before appreciated how homeopathy—whether charms, potions or medicine, is based on the principle—misguided belief that ought to be dispelled, according to Frazer, that like engenders or attracts like. The Golden Bough is pretty dismissive of such recourse, no matter how strongly ingrained but is not an exposition on other merits over mechanisms and relations, and really leaves no room for alibis for practitioners other than medicine men. It’s slow-going, but I am excited to see how the argument progresses and to see whether the self-censorship was a faithful omission.

Friday 19 June 2015

mauvaise foi

If not for coming across an indirect quotation, I would have gone on believing that the saying “Hell is other people” was a lyric from a rock-song (I’m confusing “Hell is for children” I think) and a rather throw-away sentiment and not a line, in translation, from Jean-Paul Sartre’s one-act play No Exit. Just as words might serve us better if the title of the play Huis Clos weren’t rendered as Closed Door—or rather in chambers in the legal sense of private counsel that the phrase carries in French, it would have been truer to the original if Hell was understood as the Other.

Friday 12 June 2015

instinct and individuation

It could be said that pioneering Swiss psychotherapist and collaborator of Sigmund Freud, Karl Gustav Jung, was patently his own first patient—but that can be said of most professions. Freud and Jung had an intense and productive relationship but differences in interpretation and emphasis became magnified and this strife over the nature of the psyche and best bedside-manner grew to an irreconcilable rift over a lecture tour that Jung undertook in the United States on behalf of their shared ideas.

Though Jung had his own divergent ideas about what was formative for the character and personality (de-emphasizing the role of libido and repression, Jung thought that one’s private being was a shared and public one with the collective-unconsciousness and spirituality was important component as well) he was accused of misrepresenting Freud’s theories while speaking at Fordham University (auf Deutsch to boot) but may have chosen to censor-out the sexiest bits, considering his possibly prudish audience. After the schism that formed separate schools of thought, Jung distanced himself from Freud’s thinking and shamefully denounced that favour of psychoanalysis as the Jewish science—ironically, Freud had found a great spokesman and advocate in the younger Jung initially because he came from outside that circle in Vienna and lent that the practise not be stereotyped as such: Nazism, beyond persecution, baptised many causes and individuals as undesirable even when the affiliation was in name only. Following this judgment, which understandably cast a pall over his body of work, Jung turned towards inter-disciplinary studies, in sociology, alchemy and astronomy, and embarked for years of extensive travel—trying ostensibly to get a better grasp of those shared archetypes and common-fates in mythology and creation accounts that he posited from different perspectives (modern practitioners re-branded them as the objective psyche), but to Jung’s credit, his sojourn had more humane motives, I believe, and set out to prove what was wrong with the familiar and secure Western world during the decades of the 1920’s and 30’s.

Though Jung had his own divergent ideas about what was formative for the character and personality (de-emphasizing the role of libido and repression, Jung thought that one’s private being was a shared and public one with the collective-unconsciousness and spirituality was important component as well) he was accused of misrepresenting Freud’s theories while speaking at Fordham University (auf Deutsch to boot) but may have chosen to censor-out the sexiest bits, considering his possibly prudish audience. After the schism that formed separate schools of thought, Jung distanced himself from Freud’s thinking and shamefully denounced that favour of psychoanalysis as the Jewish science—ironically, Freud had found a great spokesman and advocate in the younger Jung initially because he came from outside that circle in Vienna and lent that the practise not be stereotyped as such: Nazism, beyond persecution, baptised many causes and individuals as undesirable even when the affiliation was in name only. Following this judgment, which understandably cast a pall over his body of work, Jung turned towards inter-disciplinary studies, in sociology, alchemy and astronomy, and embarked for years of extensive travel—trying ostensibly to get a better grasp of those shared archetypes and common-fates in mythology and creation accounts that he posited from different perspectives (modern practitioners re-branded them as the objective psyche), but to Jung’s credit, his sojourn had more humane motives, I believe, and set out to prove what was wrong with the familiar and secure Western world during the decades of the 1920’s and 30’s.

catagories: 🇨🇭, 🌍, 🧠, lifestyle, myth and monsters, philosophy

gadfly or liberté toujours

Recently, I made the cast-off observation that Erasmus’ nice-making between the Catholics and the Lutherans was unwelcome on both fronts due in part to Erasmus’ reintroduction of free-will. I sort of swallowed that comment and later realised that that subject deserved a bit more attention. Most people would want to believe that they do have free-agency, free-will in at least some form, since the alternative—or at least the only one we can imagine is fate destiny, determinism or a mixture thereof—and leaves nothing praiseworthy, blameworthy, no reason to be thankful or ungracious. If one’s fate was predetermined before one was born—either by God or gods bounded by Necessity (the Fates, Μοῖραι) or in Sir Isaac Newton’s clockwork universe, bound by natural laws with all actions dependent on some antecedent action going all the way back to the beginning of time (which would apply to our own neuro-chemistry as well), it hardly seems right to consign some to eternal damnation and suffering and too to reward others in they had no choice in the matter. In more mundane terms, there is a tendency to not hold people culpable for their wrongdoings or negligence if there is found to be some pre-existing factor, like insanity or trauma or bad parenting, that absolves them of responsibility for their actions.

catagories: ✝️, 🎓, 🧠, philosophy

Thursday 11 June 2015

300 or hoplites and helots

Sparta-worship is nothing new and has gone through numerous and at times—maybe mostly, dangerous revivals. Revolutionaries as varied as those who fought for independence under the British Mandate of Palestine or under colonial Britain in North America based their extolling, exhortation and sometimes lament in failing to live up to that example on a long chain of praise that extended all the way back to times contemporaneous with the Spartan civilisation. This romancing of the austere and disciplined lifestyle practised goes by the name laconophilia (from Laconia where they lived and hence laconic or blunt) and while the course of history may have was neither steered solely by either admirers or detractors (who importantly saw the Spartans’ faults and warned that theirs was not a society to emulate) their battle-cry is heard sometimes in unexpected places. That Nazism was steeped in Nordic traditions and mythology (including fabricated volk-etymologies purely to forward their agenda) is patently well-known but I never knew that the Nazis had cast their maniacal nets further south as well and believed that the Spartans (as part of the larger “race” of Dorians) also embodied their ideal.

Sparta-worship is nothing new and has gone through numerous and at times—maybe mostly, dangerous revivals. Revolutionaries as varied as those who fought for independence under the British Mandate of Palestine or under colonial Britain in North America based their extolling, exhortation and sometimes lament in failing to live up to that example on a long chain of praise that extended all the way back to times contemporaneous with the Spartan civilisation. This romancing of the austere and disciplined lifestyle practised goes by the name laconophilia (from Laconia where they lived and hence laconic or blunt) and while the course of history may have was neither steered solely by either admirers or detractors (who importantly saw the Spartans’ faults and warned that theirs was not a society to emulate) their battle-cry is heard sometimes in unexpected places. That Nazism was steeped in Nordic traditions and mythology (including fabricated volk-etymologies purely to forward their agenda) is patently well-known but I never knew that the Nazis had cast their maniacal nets further south as well and believed that the Spartans (as part of the larger “race” of Dorians) also embodied their ideal.

Of course it was not their deportment as rational stoics or temperate individuals that held the appeal (then and now, and die neue Dorier did not go unheard) but rather the reputation of these hoplites (citizen-soldiers) on the battlefield, whose glory came at a high price—with most willing to dismiss this fascination as sophomoric, the Spartans excelling only at war through a regiment that left trainees little better than broken and brainwashed, a strict caste-system, peace untenable and dependent on a subjugated population of feudal farmers called the Helots (considered to be natural slaves). The ability to achieve and sustain this proto-fascist state through eugenics (though without the nobles lies of The Republic) was aligned with what Nazi Germany hoped to emulate, but I am not sure what brought about that political syncretism that mingled the Norse gods with Mediterranean traditions, but perhaps it was how just a few decades prior, a German entrepreneur and amateur archaeologist was able to dynamite his way to Priam’s Treasure and significantly prove to the world that there was at least a kernel of historical fact behind the legends. Feats of renown are especially prone to misappropriation.

Of course it was not their deportment as rational stoics or temperate individuals that held the appeal (then and now, and die neue Dorier did not go unheard) but rather the reputation of these hoplites (citizen-soldiers) on the battlefield, whose glory came at a high price—with most willing to dismiss this fascination as sophomoric, the Spartans excelling only at war through a regiment that left trainees little better than broken and brainwashed, a strict caste-system, peace untenable and dependent on a subjugated population of feudal farmers called the Helots (considered to be natural slaves). The ability to achieve and sustain this proto-fascist state through eugenics (though without the nobles lies of The Republic) was aligned with what Nazi Germany hoped to emulate, but I am not sure what brought about that political syncretism that mingled the Norse gods with Mediterranean traditions, but perhaps it was how just a few decades prior, a German entrepreneur and amateur archaeologist was able to dynamite his way to Priam’s Treasure and significantly prove to the world that there was at least a kernel of historical fact behind the legends. Feats of renown are especially prone to misappropriation.

catagories: 🇩🇪, 🇹🇷, 🎓, 🎬, 📚, 🧠, myth and monsters, philosophy, religion

Monday 8 June 2015

ex cathedra or east of eden

I wonder if there are different flavours within Creationist camps that are particularly bothered with one aspect of scientific theory over another. I understand that the Catholic Church—though I would not class the whole organisation with the literalists and the fundamentalists—accepts the Big Bang and Evolutionary theories nearly as incontrovertible facts and necessary for the framework of the divine’s cosmology, saying that God is not a magician with a magic wand.

catagories: 🧠, philosophy, religion

Thursday 4 June 2015

present and perdurant

Though modern Greek has adopted a more straightforward term to convey happiness, ευτυχία—just suggesting good works—the classical term Eudæmonia is fortunately still around with all its mysterious and internecine intrigues.

The greatest minds are unable to come to a consensus on what constitutes happiness (or whether that’s even a question worthy of pursuit), but I have to wonder if even the first interlocutors really knew what was meant by Eudæmonia. Semantics are of course important considerations and flourishing or thriving might be a better word than our emotionally-laden happiness—the Romans rendered it as felicitas, who was also sometimes deified, but I don’t believe that any translation could capture the sense of being a role-model compounded with a guardian angel or fairy godmother figure like the original Greek. One achieves happiness, it’s argued, by emulating the example of that demon—dæmons just being spirits, familiars or lesser deities and not diabolical ones. The nature of those qualities and whether there’s some universal imperative are hopeless elusive, though that does not mean we shouldn’t bother. Furthermore, one’s level of bliss can be impacted retroactively should one’s present deportment cause him or her to earn a bad reputation after death.

The greatest minds are unable to come to a consensus on what constitutes happiness (or whether that’s even a question worthy of pursuit), but I have to wonder if even the first interlocutors really knew what was meant by Eudæmonia. Semantics are of course important considerations and flourishing or thriving might be a better word than our emotionally-laden happiness—the Romans rendered it as felicitas, who was also sometimes deified, but I don’t believe that any translation could capture the sense of being a role-model compounded with a guardian angel or fairy godmother figure like the original Greek. One achieves happiness, it’s argued, by emulating the example of that demon—dæmons just being spirits, familiars or lesser deities and not diabolical ones. The nature of those qualities and whether there’s some universal imperative are hopeless elusive, though that does not mean we shouldn’t bother. Furthermore, one’s level of bliss can be impacted retroactively should one’s present deportment cause him or her to earn a bad reputation after death.

Thinking about these rarefied ideas in general and particularly the last bit that invokes the directionality of time makes me turn back to the novel I am currently enjoying, Jo Walton’s absolutely amazing Just City—wherein the goddess Athena gathers the prescribed youth from all ages in order to experimentally create the utopia of Plato’s Republic overseen by those who’ve prayed for wisdom. I wonder if one’s eudæmon isn’t more of a conflicted personality, like shoulder angels. The cover of the Walton’s book, incidentally, focusses in on a particular section of this larger famous fresco by Raphael—showing students engaged on the steps of the Academy below. The different elements and possible perspectives in this work of art makes me think about another of Raphael’s masterpieces, the Sistine Madonna, who’s two puti reflecting upward has become a better known detail. H and I got to see it in its entirety in Dresden once. The aforementioned fresco, however, is out of public view in the papal apartments but I recalled the style and how the tableaux extended beyond the frame, preceding into the background, as the image that was on our ticket stubs from the Vatican Museum—the ephemera buried behind too many layers of our bulletin board to excavate, just now. I don’t believe I am any closer to the being able to articulate what happiness is but do feel I’ve gone on a little trip in time just now myself.

Thinking about these rarefied ideas in general and particularly the last bit that invokes the directionality of time makes me turn back to the novel I am currently enjoying, Jo Walton’s absolutely amazing Just City—wherein the goddess Athena gathers the prescribed youth from all ages in order to experimentally create the utopia of Plato’s Republic overseen by those who’ve prayed for wisdom. I wonder if one’s eudæmon isn’t more of a conflicted personality, like shoulder angels. The cover of the Walton’s book, incidentally, focusses in on a particular section of this larger famous fresco by Raphael—showing students engaged on the steps of the Academy below. The different elements and possible perspectives in this work of art makes me think about another of Raphael’s masterpieces, the Sistine Madonna, who’s two puti reflecting upward has become a better known detail. H and I got to see it in its entirety in Dresden once. The aforementioned fresco, however, is out of public view in the papal apartments but I recalled the style and how the tableaux extended beyond the frame, preceding into the background, as the image that was on our ticket stubs from the Vatican Museum—the ephemera buried behind too many layers of our bulletin board to excavate, just now. I don’t believe I am any closer to the being able to articulate what happiness is but do feel I’ve gone on a little trip in time just now myself.

catagories: 🇬🇷, 🇮🇹, 🧠, language, myth and monsters, philosophy, Saxony, travel, Wikipedia

instant karma or everything zen

I was really kind of baffled to learn that the Laughing Buddha, a traditional fixture of Asian take-away, is in fact not the sage Gautama Buddha or an avatar thereof—like thin Elvis versus fat Elvis, but a completely different character called Bùdài.

This friendly monk represents contentment and enlightenment as well but his following developed at a time when Buddhism was taking root in a unified, ancient China and the two were conflated. I suppose the distinction is always just out of grasp for someone not intimately familiar with Eastern thought, but maybe the Buddha is the Bùdài as the Dionysian force is to Dionysis (Bacchus, the god of wine). The Buddhism that was taking root across China was also a significant departure in terms of practise from the original foundations. Thanks are owed to the bureaucratic harmonisations underlying the teachings of Confucius and his disciples, that instilled a sense of place and hierarchy that in some senses enabled disparate kingdoms and people to come under one mantle, but the revival of Buddhist thought needed some adjustments to fit to the present and enduring societal framework. As paralleled by the independent stance that monastic Ireland took towards a centralised Church authority in Rome, Buddhism as first envisioned was also meant to be a retiring one—cloistered from the illusionary, impermanent world-at-large. It surprised me even more to learn that the concept of Zen (Chàn), with a somewhat divergent but very well attested history and scholarship, was incorporated into Chinese outlook in order that each could mediate in his or her own manner and discover Buddha’s teachings—know that enlightenment is attainable in the everyday—without cossetting oneself in an abbey. While I am not sure it was exactly planned by the state (nor less authentic for it) to promote civility, there are certainly practical reasons behind it as well, since a coherent community could not very well have all its eligible men skivving off their responsibilities to hearth and home by becoming monks. There is a delicate balance, I think, between not selfishness but rather self-interestedness, that is concern for one’s salvation in private, and the civic-mindedness of seeking the same while a part of the society around one.

This friendly monk represents contentment and enlightenment as well but his following developed at a time when Buddhism was taking root in a unified, ancient China and the two were conflated. I suppose the distinction is always just out of grasp for someone not intimately familiar with Eastern thought, but maybe the Buddha is the Bùdài as the Dionysian force is to Dionysis (Bacchus, the god of wine). The Buddhism that was taking root across China was also a significant departure in terms of practise from the original foundations. Thanks are owed to the bureaucratic harmonisations underlying the teachings of Confucius and his disciples, that instilled a sense of place and hierarchy that in some senses enabled disparate kingdoms and people to come under one mantle, but the revival of Buddhist thought needed some adjustments to fit to the present and enduring societal framework. As paralleled by the independent stance that monastic Ireland took towards a centralised Church authority in Rome, Buddhism as first envisioned was also meant to be a retiring one—cloistered from the illusionary, impermanent world-at-large. It surprised me even more to learn that the concept of Zen (Chàn), with a somewhat divergent but very well attested history and scholarship, was incorporated into Chinese outlook in order that each could mediate in his or her own manner and discover Buddha’s teachings—know that enlightenment is attainable in the everyday—without cossetting oneself in an abbey. While I am not sure it was exactly planned by the state (nor less authentic for it) to promote civility, there are certainly practical reasons behind it as well, since a coherent community could not very well have all its eligible men skivving off their responsibilities to hearth and home by becoming monks. There is a delicate balance, I think, between not selfishness but rather self-interestedness, that is concern for one’s salvation in private, and the civic-mindedness of seeking the same while a part of the society around one.

Tuesday 2 June 2015

neverland

Guardian columnist Oliver Burkeman presents a tidy, provoking reflection on the latter-day manifestations with romanticising youth which really makes the alternative, natural consequence—that of growing up and growing old, appear especially bleak.

So much coddling emphasis is put upon one’s prime—as defined by marketers—that to be past it in any sense and by any sight is taken to be a sign of defeat, instead of a hallmark of grace, maturity or conviction. Rather than repairing to the nostalgic and familiar, the doom and gloom and even appealing to the hypochondriac in us as the media is either a projection or reflection—for fear we might be told we can’t keep dreaming (a measure of escapism is keen and dandy but not a whole culture of remakes, prequels and re-hashing), or becoming a retiring curmudgeon, being an adult to a big extent, I think, is about confronting the dissonance with one’s life as it is and one’s life as it should be and being able to recognise (and receive) contentment.

So much coddling emphasis is put upon one’s prime—as defined by marketers—that to be past it in any sense and by any sight is taken to be a sign of defeat, instead of a hallmark of grace, maturity or conviction. Rather than repairing to the nostalgic and familiar, the doom and gloom and even appealing to the hypochondriac in us as the media is either a projection or reflection—for fear we might be told we can’t keep dreaming (a measure of escapism is keen and dandy but not a whole culture of remakes, prequels and re-hashing), or becoming a retiring curmudgeon, being an adult to a big extent, I think, is about confronting the dissonance with one’s life as it is and one’s life as it should be and being able to recognise (and receive) contentment.

catagories: ⚕️, 🧠, lifestyle, philosophy

Monday 1 June 2015

palabra jot

Just as the kingdoms of Heaven and the Earth were already careening in directions unknown with the confluence of Martin Luther’s critical and revolutionary stance, Henry VIII’s dissention that led to the Anglican confession, the discovery of the New World materialising and successive plagues picking off large swaths of the impious and faithful alike, the event that probably shook the foundations of the Church the most was a conciliatory bearing, a compromise characterised as a Middle Way, advocated by one of its own, Dutch theologian and scholar Desiderius Erasmus.

In the spirit of Cicero, regarded as the father of humanism, Erasmus championed dialectic over pure dogma and believed that religion revealed rather than one imparted made one’s belief genuine and steadfast—although Erasmus did not go as far as Luther in abolishing the priestly class, maintaining that tutors were necessary. Furthermore, raising more contention with the Protestant movement than reconciliation, Erasmus argued that that personal, less mediated relation with the divine was not consequent to the notion of predestination, accepting that one is part of God’s plan and happy with that, but instead that the orthodox idea of free will (which is not unfettered agency but the ability to see outcomes as otherwise than they actually turn out—that is, understanding that one’s actions and intentions have consequences, for good or evil) still had a place in this reformed cosmology. The most public and controversial act of the academic, however, was his decision to brush up on his Greek and Latin (the stock-phrase Pandora’s box comes from one of Erasmus’ earlier, honest mistranslations of Hesiod—it ought to be Pandora’s jar) and undertake to produce a definitive new translation of the Bible, since Luther’s own (thanks to the advent of the printing-press) was a popular success and successful too in promulgating historic typos. Luther, as King James and virtual all theologians relied on the four century translation of Saint Jerome of the Greek testaments into Latin. Wanting to provide his parishioners as pupils a better text and feeling admittedly divinely inspired, Erasmus quipped that “it is only fair that Paul should address the Romans in somewhat better Latin” and began his new version. Though a traditionalist in terms of Church politics, Erasmus did a poor job in restraining himself when it came to language. While I am sure that all linguists of any ilk sort of cringe to find surpassing λόγοϛ rendered as plain old word (Verbum), it was just too much for the Church to take when the first proofs started, very first chapter and verse, “In the beginning there was Conversation…” It is hard to say if Erasmus and his adherents might have negotiated a more peaceful and civil schism or might have made matters far worse, but both sides rejected this agitator’s backing as too much of a liability.

In the spirit of Cicero, regarded as the father of humanism, Erasmus championed dialectic over pure dogma and believed that religion revealed rather than one imparted made one’s belief genuine and steadfast—although Erasmus did not go as far as Luther in abolishing the priestly class, maintaining that tutors were necessary. Furthermore, raising more contention with the Protestant movement than reconciliation, Erasmus argued that that personal, less mediated relation with the divine was not consequent to the notion of predestination, accepting that one is part of God’s plan and happy with that, but instead that the orthodox idea of free will (which is not unfettered agency but the ability to see outcomes as otherwise than they actually turn out—that is, understanding that one’s actions and intentions have consequences, for good or evil) still had a place in this reformed cosmology. The most public and controversial act of the academic, however, was his decision to brush up on his Greek and Latin (the stock-phrase Pandora’s box comes from one of Erasmus’ earlier, honest mistranslations of Hesiod—it ought to be Pandora’s jar) and undertake to produce a definitive new translation of the Bible, since Luther’s own (thanks to the advent of the printing-press) was a popular success and successful too in promulgating historic typos. Luther, as King James and virtual all theologians relied on the four century translation of Saint Jerome of the Greek testaments into Latin. Wanting to provide his parishioners as pupils a better text and feeling admittedly divinely inspired, Erasmus quipped that “it is only fair that Paul should address the Romans in somewhat better Latin” and began his new version. Though a traditionalist in terms of Church politics, Erasmus did a poor job in restraining himself when it came to language. While I am sure that all linguists of any ilk sort of cringe to find surpassing λόγοϛ rendered as plain old word (Verbum), it was just too much for the Church to take when the first proofs started, very first chapter and verse, “In the beginning there was Conversation…” It is hard to say if Erasmus and his adherents might have negotiated a more peaceful and civil schism or might have made matters far worse, but both sides rejected this agitator’s backing as too much of a liability.

catagories: ✝️, 🌍, 🎓, 🧠, language, philosophy, revolution, Wikipedia

Friday 22 May 2015

dozy doats oder extra-sensory

The village just west of Wiesbaden probably got its name (and crest, a “T”) owing to a count of the court of King Dagobert I called Tuzzo, but the designation Dotzheim was to become an important aristocratic line under the rule of the House of Nassau in its own right and the cast-iron mascots, Dotzi, hung on many of the older buildings at the town centre.

The village just west of Wiesbaden probably got its name (and crest, a “T”) owing to a count of the court of King Dagobert I called Tuzzo, but the designation Dotzheim was to become an important aristocratic line under the rule of the House of Nassau in its own right and the cast-iron mascots, Dotzi, hung on many of the older buildings at the town centre.

A bit further on (which is why I needed to split up my walk—plus it started to rain) one encounters Schloss Freudenberg—which, for being only built in the early 1900s, has a pretty extensive and complex history. It was completed in 1903 but the youngest castle in Germany dates from 1908, and is included in this collection. The mansion was commissioned by a Scottish post-impressionist painter and his wife but they only lived there a few years—to be later appropriated as a home for expectant mothers and young children of the Lebensborn programme.

A bit further on (which is why I needed to split up my walk—plus it started to rain) one encounters Schloss Freudenberg—which, for being only built in the early 1900s, has a pretty extensive and complex history. It was completed in 1903 but the youngest castle in Germany dates from 1908, and is included in this collection. The mansion was commissioned by a Scottish post-impressionist painter and his wife but they only lived there a few years—to be later appropriated as a home for expectant mothers and young children of the Lebensborn programme. During the course of the war, a garrison was built up on the surrounding gardens near this railhead and was afterwards occupied by the US forces. Freudenberg became an officers’ club and casino until 1973 when it abandoned and fell in disrepair.

During the course of the war, a garrison was built up on the surrounding gardens near this railhead and was afterwards occupied by the US forces. Freudenberg became an officers’ club and casino until 1973 when it abandoned and fell in disrepair. The castle was saved from ruin by a group of adherents to the philosophy of Hugo Kükelhaus, who turned the estate into playground for the senses. Kükelhaus along with his promoted exercising ones perceptions to the fullest in order to hone ones imagination and understanding of the world and eschewed the sanitary, inhuman architecture and design that confined and exhausts by removing those things we are made to feel.

The castle was saved from ruin by a group of adherents to the philosophy of Hugo Kükelhaus, who turned the estate into playground for the senses. Kükelhaus along with his promoted exercising ones perceptions to the fullest in order to hone ones imagination and understanding of the world and eschewed the sanitary, inhuman architecture and design that confined and exhausts by removing those things we are made to feel. Several permanent installations, called experience stations (Erfahrungsfelder), are on display.

The ongoing renovation project itself is also an extension of Kükelhaus’ beliefs and is therapeutically defined as the combination of healing and art. There is the further objective of educating visitors in abstractions that are independent of the powers of perception (by cultivating and refining one’s physical senses as much as possible) so that they might apprehend what’s just beyond—like dignity and equality.

The ongoing renovation project itself is also an extension of Kükelhaus’ beliefs and is therapeutically defined as the combination of healing and art. There is the further objective of educating visitors in abstractions that are independent of the powers of perception (by cultivating and refining one’s physical senses as much as possible) so that they might apprehend what’s just beyond—like dignity and equality.As well as being the home and headquarters of Hugo Kükelhaus’ movement, Schloss Freundenberg hosts regular seminars and events for kindred organisations and schools of thought. By rushing through I suppose that I was completely missing the point by not playing and discovering fully, but when there is more time, I certainly plan to return and experience all the textures and trapezes.

catagories: 🇩🇪, 🌍, 🎓, 🧠, environment, Hessen, philosophy

Tuesday 19 May 2015

bypass or great big convoy

Via the ever-excellent Kottke comes this rather profound study and projection of how self-driving vehicles will alter the economy and particularly the gas-food-lodging infrastructure built to support commercial trucking. While it does not take much boldness to imagine a phalanx of safer, more efficient robot guided convoys taking truckers out of the drivers’ seats as it has already come to pass, but the impact does not of course stop with this last lament of middle-class bread-winners.

The article is written from an American perspective and by analogy compares the seismic changes that could occur to those communities that the interstate freeway system passed by and withered for the sake of expedience, but I think the analysis is completely universal. With manufacturing increasingly retreating into yonder tightfistedness, goods are forever being shuttled back and forth. Consuming merchandise created and delivered by machine, vast swathes of the human workforce (and ultimately, all of it) become redundant and without access to meaningful employment. The untenable situation is accelerating to an important junction, wherein either there is no demand to satisfy the production-capacity because no one has the tender to pay for it or money becomes a rather meaningless trifle and in a utopian society, humans are at last allowed to enjoy the fruit of their labour. I suppose that’s precisely the point of progress but it is hard for me to imagine that the robber-barons might herald this event joyfully—especially if they knowing ushered in their own severance. What do you think? Will those automated cars drive us all off a cliff or make our existence better by abolishing capital?

The article is written from an American perspective and by analogy compares the seismic changes that could occur to those communities that the interstate freeway system passed by and withered for the sake of expedience, but I think the analysis is completely universal. With manufacturing increasingly retreating into yonder tightfistedness, goods are forever being shuttled back and forth. Consuming merchandise created and delivered by machine, vast swathes of the human workforce (and ultimately, all of it) become redundant and without access to meaningful employment. The untenable situation is accelerating to an important junction, wherein either there is no demand to satisfy the production-capacity because no one has the tender to pay for it or money becomes a rather meaningless trifle and in a utopian society, humans are at last allowed to enjoy the fruit of their labour. I suppose that’s precisely the point of progress but it is hard for me to imagine that the robber-barons might herald this event joyfully—especially if they knowing ushered in their own severance. What do you think? Will those automated cars drive us all off a cliff or make our existence better by abolishing capital?

catagories: 💱, labour, philosophy, revolution, technology and innovation, transportation

Monday 18 May 2015

circe or the call of the wild

Intrepid explorer Colonel Percy Harrison Fawcett first became enamoured with South America and the allure of the dense, uncharted jungles when as a surveyor was invited to help resolve a border dispute between Brazil and Bolivia. Some twenty years after the initial encounter (with World War I intervening), Fawcett resolved to return, ostensibly, to seek out a mid-eighteenth-century anecdote he’d learned of: a slave-trader who’d come across a mysterious city deep in the jungles. Braving the elements, predation and potentially hostile tribes, Fawcett assembled a small expedition and embarked to find this place he called the Lost City of Z.

catagories: 🇬🇧, 🌎, 🎓, myth and monsters, philosophy, religion

Wednesday 13 May 2015

grooks or squaring the circle

During the Nazi occupation of Denmark poly-math turned resistance-fighter by the name of Piet Hein published thousands (a body of some seven-thousand in his lifetime) of short, aphoristic poems that really went above the heads of their oppressors but were immediately understood and spread virally by the Danish people. Hein called these concentrated verses grooks (gruks, which Hein maintained was purely a nonsense word but some suggest it is a portmanteau of laugh plus sigh) and one particularly poignant one illustrates the heartbreak of conquest, vacillating between indecision, flight or taking up arms:

There are multitudes to discover on every subject and I am sure that anyone could find one that resonates.

Or for the melancholy Dane, finding resolve when least expecting it:

and you're hampered by not having any,

After the war, Hein continued to formulate grooks of course but also turned his attention to other word play in the form of language games and logic puzzles. Returning to his mathematical and engineering prowess, having mentally spared with Niels Bohr and other luminaries, Hein also devised an architectural compromise that embraced both the rectilinear and the round in the form of what’s called the superegg, which came to typify Scandinavian Mid-Century design and architecture.

Tuesday 12 May 2015

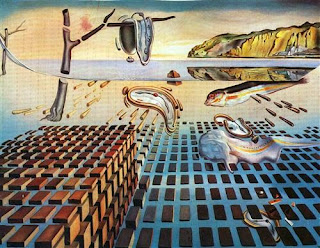

lifecycle replacement or persistence of memory

The whole time I was enjoying Doug Dorst’s frame novel S, I did not realise that the subtitle, The Ship of Theseus, was itself a reference to a rather famous philosophical model.

catagories: 📚, philosophy, Wikipedia

Thursday 7 May 2015

a penny saved is twopence dear

I learnt of a gem of non-canonical, being that it’s not part of his main body of writing—like Poor Richard’s Almanack of proverbs and other achievements, both genuine and attributed, wisdom discovered in the correspondence of statesman Benjamin Franklin, writing to a friend from his diplomatic post in Paris. In his golden years, Franklin recalled a fundamental episode from his early youth. The story Franklin tells and the aphorism it lends itself to—paying too much for one’s whistle (in reference to an impulse-buy that ended up bringing more post-shopping regret than pleasure)—is as memorable and astute as any. One can read the letter in its entirety here with Franklin’s inventory of poor souls whose vanities have cost them dearly. I do suppose, too, it is easier to recognise such folly of others rather than to confront it in ourselves.

I learnt of a gem of non-canonical, being that it’s not part of his main body of writing—like Poor Richard’s Almanack of proverbs and other achievements, both genuine and attributed, wisdom discovered in the correspondence of statesman Benjamin Franklin, writing to a friend from his diplomatic post in Paris. In his golden years, Franklin recalled a fundamental episode from his early youth. The story Franklin tells and the aphorism it lends itself to—paying too much for one’s whistle (in reference to an impulse-buy that ended up bringing more post-shopping regret than pleasure)—is as memorable and astute as any. One can read the letter in its entirety here with Franklin’s inventory of poor souls whose vanities have cost them dearly. I do suppose, too, it is easier to recognise such folly of others rather than to confront it in ourselves.

catagories: 🇫🇷, 🇺🇸, 🎓, 📚, philosophy

Monday 4 May 2015

shangri-la or a chicken in every pot

I was listening to a pretty interesting, if not rather sedate but being shrill does not presuppose being impassioned, podcast from BBC Radio 4’s In Our Time segment on the notion of Utopia. Many shun such rarefied discussions as purely academic and formal and human pursuits are not the staid stuff of quiet questioning—just something that we’ve named though cannot agree on the definition, however this panel show was particularly interesting as the episode had originally been broadcast in 1999, on the cusps of the new century and classic thought was indeed buffeted with a lot of future-forward and progressive predictions.

The term utopia is a bit of a puzzle in itself, sounding like έΰ-τοποζ (good-place) but introduced to describe a society that was nowhere (ου)—I don’t think that this was intended as some cynical pun but rather an admonition not to confuse the merely good with the best or the ideal. Even if it did point us to no place, nonpareil, it still gave us visions to aspire to—which were of course constrained by writers’ imaginations and the context that they were writing in. There was much fear and suspicion over perfect societies and technology’s role in creating them—as there is today, thinkers having witnessed the ways regimes can pervert mechanisation and eugenics to forward their own agenda and ideal. In speculative fiction and reality, many of these efforts have backfired in dystopia ways. Having every need and want fulfilled and a surplus leisure seems appealing, but by many past reckons, we are living in an era of great ease and security, the promise of realized of some authors’ reveries—or at least progressing there, yet we seem more and more dissatisfied. Eventually the talk came around to categorizing futurists into two camps as to how this revelation might be achieved: the husbanders and the technocrats.

The term utopia is a bit of a puzzle in itself, sounding like έΰ-τοποζ (good-place) but introduced to describe a society that was nowhere (ου)—I don’t think that this was intended as some cynical pun but rather an admonition not to confuse the merely good with the best or the ideal. Even if it did point us to no place, nonpareil, it still gave us visions to aspire to—which were of course constrained by writers’ imaginations and the context that they were writing in. There was much fear and suspicion over perfect societies and technology’s role in creating them—as there is today, thinkers having witnessed the ways regimes can pervert mechanisation and eugenics to forward their own agenda and ideal. In speculative fiction and reality, many of these efforts have backfired in dystopia ways. Having every need and want fulfilled and a surplus leisure seems appealing, but by many past reckons, we are living in an era of great ease and security, the promise of realized of some authors’ reveries—or at least progressing there, yet we seem more and more dissatisfied. Eventually the talk came around to categorizing futurists into two camps as to how this revelation might be achieved: the husbanders and the technocrats.

Although it was not so long ago and not a retro-future sort of prophesy (which lend us a world far better than what we’ve achieved), it was very interesting how the two groups, geneticists and artificial-intelligence proponents argued their cases. While we do speak in terms of the singularity today, a relinquishing control to a thinking-machine and trust it to keep human welfare as its pet-project and maybe engineer that ideal society, rather than slum around with the details, it is interesting how the panel framed and previsioned their creature-comforts. One side argued that genetic understanding would produce a class of beings where the fittest were not only the most competent but also the kindest and most generous (since the best and most efficient way to promote the individual is not only to fool one’s competition but moreover to fool oneself into being altruistic). The technologists, on the other hand, argued that surrendering day-to-day tasks to a network of computers that monitored our needs and health would greatly increase our efficiency in all things and eventually put us among the stars. Though there are some contemporary persuasive voices urging mankind to become space-faring whom might have become better know, it’s interesting that the proponent that they knew was the physicist Freeman Dyson, who believed that humans should hollow out comets and travel, sheltered, across the Universe like the Little Prince. What do you think? Has AI and our inter-connectedness made utopia and related concepts rather moot points?

Although it was not so long ago and not a retro-future sort of prophesy (which lend us a world far better than what we’ve achieved), it was very interesting how the two groups, geneticists and artificial-intelligence proponents argued their cases. While we do speak in terms of the singularity today, a relinquishing control to a thinking-machine and trust it to keep human welfare as its pet-project and maybe engineer that ideal society, rather than slum around with the details, it is interesting how the panel framed and previsioned their creature-comforts. One side argued that genetic understanding would produce a class of beings where the fittest were not only the most competent but also the kindest and most generous (since the best and most efficient way to promote the individual is not only to fool one’s competition but moreover to fool oneself into being altruistic). The technologists, on the other hand, argued that surrendering day-to-day tasks to a network of computers that monitored our needs and health would greatly increase our efficiency in all things and eventually put us among the stars. Though there are some contemporary persuasive voices urging mankind to become space-faring whom might have become better know, it’s interesting that the proponent that they knew was the physicist Freeman Dyson, who believed that humans should hollow out comets and travel, sheltered, across the Universe like the Little Prince. What do you think? Has AI and our inter-connectedness made utopia and related concepts rather moot points?